When journalists tell stories through visuals, there are a lot of options for where to turn. There are also a variety of ways to capture a photo, edit a video, and share visual content. The bottom line: A lot of decisions are made by journalists and newsrooms related to the types of visual content they […]

Build trust with your photos and videos

When journalists tell stories through visuals, there are a lot of options for where to turn. There are also a variety of ways to capture a photo, edit a video, and share visual content.

The bottom line: A lot of decisions are made by journalists and newsrooms related to the types of visual content they publish. A lot of those decisions are related to newsroom policies or ethical journalism standards that most journalists have been adhering to for decades.

Unfortunately, the public is not as familiar with these policies or standards. Some think an ethical standard focused on visual content doesn’t exist in the industry. How can journalists change this? By talking publicly about what their policies are related to visual content and explaining how they work to be fair and accurate while minimizing harm when publishing images and video.

At Trusting News we would like to see more journalists and news organizations go on the record about these core elements related to visual news content:

- How photos/videos are edited

- Where photos/videos come from

- How people end up in photos/videos published by news organizations (and if they can ask not to be included)

- What being a visual journalist is like

This post provides some tips and ideas for answering these questions while getting on the record about the journalistic values and ethics related to photos and video.

These tips and ideas first appeared as a series in our Trust Tips newsletter. While preparing for the series, it was harder than expected to find clear examples of news organizations talking about how they approach editing and selecting visuals. If you talk publicly about your use of photos and videos or have seen a good example of a newsroom being transparent about its visual policies, let me know: Lynn@TrustingNews.org.

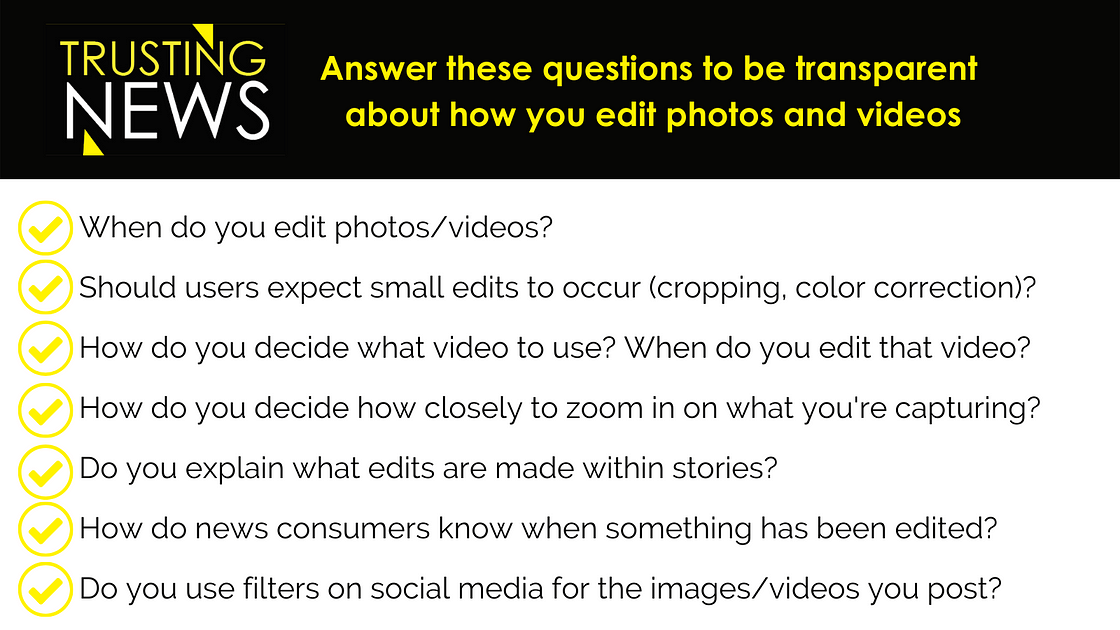

1. Explain how you edit photos/videos

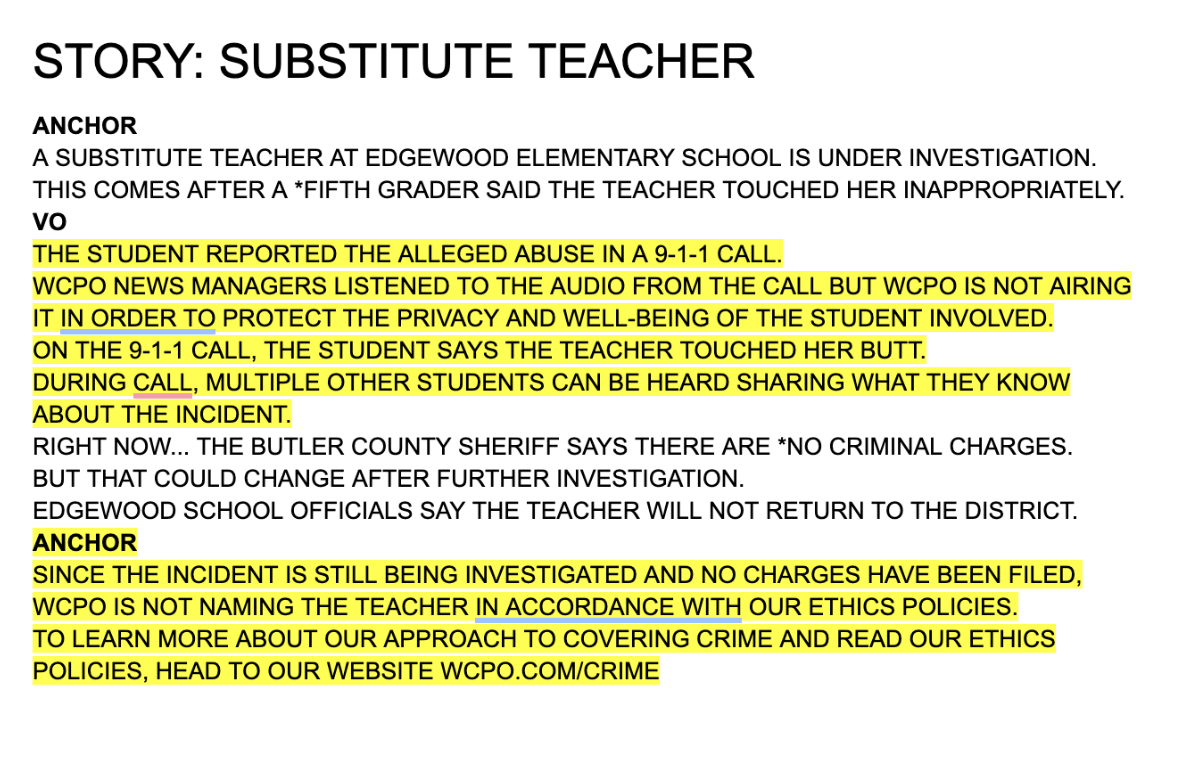

You’ve probably heard the criticism or accusations before: You edited that photo to purposefully not show the whole scene, or you purposefully cut the video before they made their point.

Accusations like these are all too common, and it won’t surprise you to know that our advice is to address these accusations publicly. The criticism has seemed even more prevalent during the pandemic. When faced with criticism or accusations, some journalists have responded.

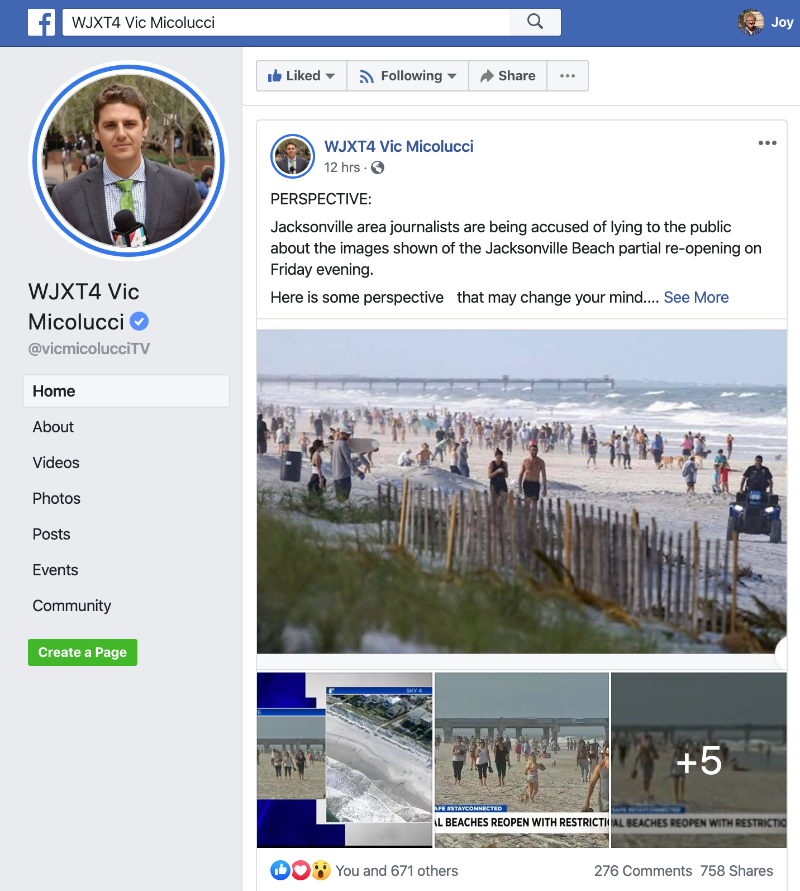

Including reporter Vic Micolucci of WJXT in Jacksonville. As rumors swirled that local journalists had altered photos of beaches reopening in Florida during the coronavirus pandemic, Micolucci decided to address accusations directly in a Facebook post. He included several images and explained the differences between them based on angle, camera and lens choices.

“Kindly lay off local journalists working hard to cover a situation. I can assure you almost all of us, my competitors included, have good, honest intentions of keeping you informed and safe. A helicopter shot looks different from a drone shot which looks different from a telephoto shot which looks different from a smart phone shot. The optics are different. The angles are different. As your car mirrors say, objects may appear further than they are. Use your best judgement.”

His explanation is thorough and honest. To take it a step further, what if Micolucci could link back to a public-facing policy explaining the newsroom’s approach to photos/videos? Without these public explanations, news consumers are left wondering what journalists edit, if they edit and how they edit. And, when they are left to wonder, they are likely to assume the worst: that we edit to fit a narrative or an agenda.

Instead of leaving them to wonder, what if we explained some of these questions:

- How do you edit photos/video? Should users expect that there is normally some type of small edit happening (cropping, color correction)? How do they know if more has been done to a photo or video?

- How do you decide what video clips to use for b-roll? How do you edit that video?

- How do you decide how closely to zoom in on the scene you’re capturing?

- Do you explain what edits were made to photos/video within stories? How can a news consumer know when something has been edited?

- Do you use filters on social media for the images/videos you post?

Having spent a lot of time talking to and working with photographers and videographers, I know there are high ethical standards for what is appropriate and acceptable when it comes to editing. But, that standard is not always the same and can vary from newsroom to newsroom and even within a newsroom.

A standard set by the National Press Photographers Association (NPPA) code of ethics related to editing says, “Editing should maintain the integrity of the photographic images’ content and context. Do not manipulate images or add or alter sound in any way that can mislead viewers or misrepresent subjects.”

This is a great start to help answer some of those questions above. Remember, just talking about and making news consumers aware you are thoughtful about the work you do and the decisions you make can help build trust. If newsrooms just started by saying they follow the standard set by NPPA, I think it could make a difference in the perception of how journalists approach photos and videos.

Adding a little more information would be even better, though. What if you explained that you follow NPPA’s code and then provided a few examples of edited visuals along with a brief explanation of why the edits were made? This could help news consumers better understand why edits are made.

If you wanted to go a step further in your transparency around visuals, you could alert news consumers when something has been edited and include a brief explanation as to why it was edited. Remember, explaining policies or ethics in one post or on a section of your website is great, but if you don’t link to those explanations in the stories (or in this case images/videos) where they apply, people are very unlikely to see those explanations and ethics.

2. Be clear about where photos and videos come from

When journalists use visuals in their stories there are a lot of options for where to turn. We routinely shoot photos and videos as part of our daily coverage, of course. But we also turn to our archives, run images from social media and rely on visuals from sources.

Our selection process often involves a lot of careful and thoughtful decisions by multiple people in a newsroom. We weigh which visuals tell the story most effectively of course. And we consider legal consequences involving copyright and fair use. We think about ethical consequences like how people in the photos or video may be impacted or if the visuals are appropriate to share publicly at all.

As with other daily decisions, we can take for granted these factors and forget they’re not obvious to the public. Instead, we really should talk more about the process publicly. When thinking about the use of photos and videos in stories, two main questions seem to be the most important to answer for users:

- Where did the photos/video come from?

- Why did we choose these visuals?

A lot of times those questions can be answered in a caption or with proper labeling. But as an industry, we aren’t always very consistent with those practices. Let’s look at how we could prevent a lot of guessing and questions from users, which can lead to accusations and criticism.

Some ways we can be consistent with explaining visuals:

- Make sure visuals from the archives and file footage are always labeled as such. A user should know when they are looking at something that wasn’t captured as part of the story it’s associated with. Adding dates and locations is important as well.

- Commit to writing captions that describe what is in the photo/video. Also, make a connection between why the visual is relevant for the story it’s associated with. In most cases, that connection is pretty obvious, but sometimes an explanation is needed to help news consumers connect the dots. Larry Kutner, a Trust Tips subscriber and former TV news reporter/producer put it this way: Does the audience have the ability to derive the context for the use of the visuals? Do the visuals serve a purpose or are they simply “good video”?

- Be clear about who took the photo or recorded the video. If it was recorded by someone in your newsroom, make that clear (and a name alone is not enough — say “Jeff Smith, ABCD Photojournalist”). If it came from social media, be sure that is clear. (Even better, link to an explanation about why you sometimes use photos from social media, how that process works, how you fact-check content and how people can submit their own photos/videos.)

- If something is graphic or explicit, make sure the proper labels are on the content. Make sure those labels follow the content everywhere it is used.

While labeling and well-written captions might add the needed transparency and information in a lot of cases, sometimes the visuals you choose to use need more of an explanation.

USA TODAY found themselves in a situation of needing to offer more of an explanation when the heartbreaking photos of a young dad and his toddler who drowned trying to cross the border into the United States emerged.

The network’s news organizations had to make the difficult decision of whether they would show the graphic photo alongside their reporting. When USA TODAY made the call that they would run the photo, the standards editor at the time, Manny Garcia, wrote a column explaining the reasoning behind the decision.

“This is a story that must be told — fully and truthfully, with context and perspectives from all sides … Death is a constant along the border, but rarely is it captured in such a direct way.”

It’s likely the column got much less traffic than the actual news story itself, leading to the assumption that a lot of readers didn’t see or know the level of thought the paper put behind this decision to run the graphic photo. To level up, we recommend including a sentence about the decision and linking to the column in the caption of the photo itself. That way the explanation would appear alongside the photo in every story it was attached to.

Some other common instances where a longer explanation may be worthwhile: the use of police body camera video (how did you get it, is it edited, did you remove graphic content, etc.) or any images or video obtained through public record laws, the courts (a video deposition or evidence images), neighborhood doorbell cameras, surveillance cameras, etc.

3. Talk about how people end up in your photos and videos

Don’t journalists pay the people who appear in their video stories or photographs? That’s a common misassumption we have heard from news consumers. When I first heard this, I was really surprised, mostly because I know how tight newsroom budgets are and what journalists are paid. Where would the money to pay all of these people come from?

But, if someone doesn’t have an understanding of the financial landscape of the journalism industry, thinking someone is paid for being in the newspaper or on TV isn’t a far stretch. Models get paid, and actors and actresses get paid. So, how is that different than what they see on their local news or the news photos online?

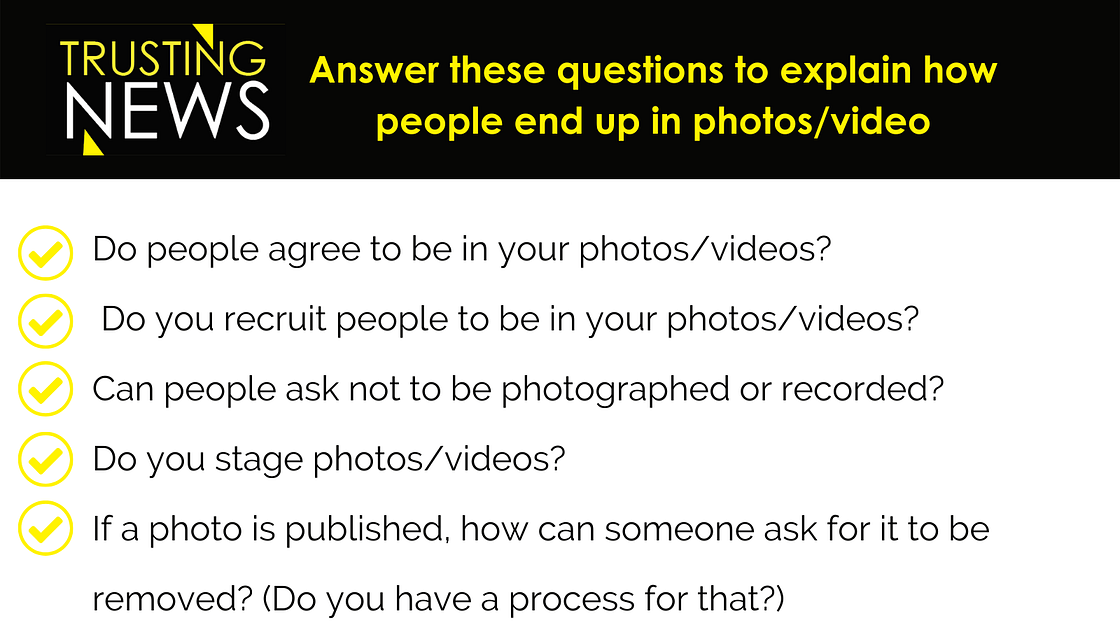

People have a lot of questions when it comes to how people end up on TV or in photos in a newspaper or on a news organization’s website. As journalists, we should be explaining questions like:

- Do people agree to be in your photos/videos?

- Do we recruit people to be in your photos/videos?

- Can people ask not to be photographed or recorded?

- If a photo of someone is published by your news organization, how could someone ask for it to be removed? (Do you have a process for that?)

- Do you publish photos of minors? Crime victims? Mug shots?

- Do your decisions differ based on how prominently someone is featured in the images?

- Do you stage photos/videos for stories?

The answers to these questions aren’t always black and white. There can be a lot of nuances involved. For example: Often, we will get an individual’s name after taking their photo. This isn’t an agreement in a formal sense but in many cases serves as our way of letting them know who we are and that we took their photo for our news organization. But, not all situations allow for that (protests, large events, etc.), and sometimes by being at a public event they have given consent to being photographed and may not even know it.

So, do people agree to be in our photos/videos? It kind of depends on the circumstances, right? Wouldn’t it be great if we explained that?

As journalists, we could explain that while, yes, it can depend on the circumstances of the moment, normally we are thinking carefully and considering our values and ethics when making decisions about who we include in our photos and videos.

We could also explain what people should expect if they see a photographer from our newsroom. We could explain what our rights are as journalists when it comes to taking photos and videos. We also should explain what the public’s rights are. There is often confusion around what rights an individual has when out in public. Often, there is an expectation of privacy that just doesn’t exist. We should explain this to our communities.

We should also talk about what our approach is in situations like a protest or a large event happening on public property. While it may be legal for us to take an individual’s photo or show them in our live feed, we may sometimes decide not to, due to our ethics. This topic has been discussed in the journalism community many times in recent years, but, now, I think it’s time for news organizations to share publicly how they approach these situations.

Ideally, news organizations have an FAQ or section on their ethics or “About Us” page that addresses visuals, specifically, how the news organization asks permission or doesn’t (because of public property) when taking a photo or shooting video. The next step would be to link these explanations in stories when appropriate and maybe even have small handouts for video journalists and photographers to share when they are out in the community.

4. Encourage visual journalists to talk about their experiences

There is a lot to explain when it comes to how journalists decide what photos and videos to publish. Some of those explanations can be pulled from newsroom policies or journalism ethics codes. But, some of what is unknown and worth explaining to your audience has to do with the role of a photojournalist. And explaining what that means can be best accomplished by having photojournalists talk personally about their role and goals as a journalist.

Some elements worth explaining could be:

- They serve as a witness. They show up to a scene and capture what they are seeing. Yes, sometimes that means they are capturing everything that’s happening even if it is hard to watch. Have photojournalists talk about what it’s like to capture intense moments of sadness, pain, anger, etc.

- What responsibility comes with witnessing? Journalists often see the role of photographers and videographers as one of holding up a mirror to what’s happening in the community. But, ultimately there is a choice of either to record or take a photo or not. How do photojournalists make those decisions? Do they ever feel the need to act while witnessing something? Have they ever acted? Also, while they sometimes might capture what is happening, that doesn’t mean it always gets published. What is it like to make those decisions?

- They have a front-row seat to history. Every photojournalist I’ve worked with takes the responsibility of having a front-row seat to history seriously. I wish more would talk publicly about this.

- They can put themselves in harm’s way. People may not understand how photojournalists put themselves in harm’s way to capture images and videos for the stories newsrooms publish. Yes, all journalists do this to some extent, but photojournalists can be in positions where the risk of harm happens more often. It can be a dangerous job. This happened often during COVID. When other journalists were able to work from home, photojournalists and videojournalists were on the front line, something the San Francisco Chronicle wrote about.

- What they witness is sometimes unbelievable. Sometimes the truth really is stranger than fiction. Photojournalists may find themselves in awe or shocked by what they are seeing. They are experiencing what is happening in real-time. How do they process what they see? Has being on the front lines changed their perspective?

Earlier this year, John Spink, a photojournalist for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, wrote about what it’s like documenting homicides. He explains that while he is close to the scenes of the deaths, he’s not as close as the police and other first responders. He says it is an “exercise in documenting police work” but can become emotionally charged quickly when friends or family are present.

My two favorite parts of the article are when John explains the role a journalist has in these situations and when he discusses what he does while at the scene.

He describes the role of a journalist this way:

“As a journalist, it’s in these moments you enter into a zone, respectfully and discreetly making images of reactions of family and friends as they break down and console one another. These images of grief and anguish usually hit readers the most. Homicide victims are not statistics. They are people who had family, co-workers and friends.”

He then describes something he does while at the scene:

“I decided a long time ago that I would not just take photos and take information from the scenes of homicide investigations. I had to give something while I was there. Aside from something journalistically, that something I do is spiritual. I pray the grieving families’ burdens may be lightened and mercy cover their loved ones. I even pray for the perpetrators, as radical as that seems. Christian ethics demand prayer for our enemies. Even murderers like Moses and Saul were given the time and grace to change. And eventually, they became great lights for good. My prayer for a perpetrator is that their prison cell become a monastery.”

This story lets people see what it’s like to be a photojournalist. It also lets users learn more about John and how he approaches his work. It’s authentic and honest. Content like this can be written in a story, but it could also be shared on social media as social cards or a Twitter thread, or in the text of social posts.

Trusting News would like to thank the following journalists for offering insights for this series: Nicole Frugé, Director of Visuals for the San Francisco Chronicle, Peter Huoppi, Director of Multimedia for The Day, Emilie Stigliani, Executive Editor for the Burlington Free Press, Mike Canan, Director of Journalism Strategies for the Scripps Howard Foundation, Patrick Boehler, Digital Strategy for Radio Free Europe, Ruth Serven, Editor for the education desk for Al.com and Susan Potter, Political Editor for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

At Trusting News, we learn how people decide what news to trust and turn that knowledge into actionable strategies for journalists. We train and empower journalists to take responsibility for demonstrating credibility and actively earning trust through transparency and engagement. Subscribe to our Trust Tips newsletter. Follow us on Twitter and LinkedIn. Read more about our work at TrustingNews.org.

Assistant director Lynn Walsh (she/her) is an Emmy award-winning journalist who has worked in investigative journalism at the national level and locally in California, Ohio, Texas and Florida. She is the former Ethics Chair for the Society of Professional Journalists and a past national president for the organization. Based in San Diego, Lynn is also an adjunct professor and freelance journalist. She can be reached at lynn@TrustingNews.org and on Twitter @lwalsh.