HOW NEWS WORKS

Explain your sourcing

Of all the dozens (or hundreds, or thousands) of people you could have talked to for any given story, why did you choose the ones you did? Were they uniquely qualified? If so, how do you know? Did they represent a diverse range of perspectives? If so, why did that matter to you? Did they bring specific expertise or credibility? If so, what was it? Did they show themselves to be speaking from a place of integrity, not from any outside, undisclosed interest? If so, how do you know? Or were they just the most convenient?

We know that when the public doesn’t understand something about journalism, they draw their own conclusions — and those conclusions don’t often give journalists the benefit of the doubt. Instead, people assume we choose sources to push a specific angle, to support our own (or the sources’) agenda, to make one side of a story look bad or good, etc. They might also assume that people are quoted in our stories just because they were nearby and available (which is sometimes true, right?).

As with other misassumptions about the ethics and processes involved in our work, it’s up to us to get on the record explaining ourselves.

Journalists usually have reasons for interviewing and quoting specific sources, but those reasons are invisible unless we explain them.

Goals

People would find journalism more credible if they understood things like:

- How we choose people to be sources

- How we choose other sources of information to cite from, such as research, documents and polls

- How we decide what information to share about sources

- How we try to reach sources and be fair to people featured in stories

Things to explain

It’s time to get in the habit of explaining your sourcing.

Look at the below list of questions. Think about what things your audience might be the most confused about, and prioritize answering those questions. Click or tap the blue boxes to expand each section.

How do you decide which experts to interview?

Out of all the (professors/plumbers/doctors/teachers) out there, why did you choose to interview the ones you did? Were they recommended by someone? Do they have unusual credentials? Has their work or experience been especially relevant to the topic? Also, did you double-check their information against what others in their field have said to make sure their information was verifiable before including it? If so, say so!

How do you decide which regular people to interview?

When journalists use individual people in stories to represent large groups, there’s often a fairly random process for who gets included. Which person at the weekend festival gets interviewed? Which parent at school fundraiser? Which neighbor weighing in on traffic patterns? Which people exiting a polling place?

The key here is not to make an ironclad case for why those people were the precise right people. It’s to acknowledge your methodologies (and sometimes your limitations). See if you can work into your story a mention that you talked to people around the festival for an hour, and here’s a collection of what you heard. Or you visited two polling places looking for people with different perspectives to share. Or you talked to several people who didn’t feel comfortable talking publicly about their views, but here are three who were willing to share.

How do you work to be mindful of source diversity?

Does your newsroom have a commitment to featuring voices that reflect the complexity and diversity of the community overall? If so, what does that look like? Do you track source diversity, informally or systematically? Do you ask sources questions about their background and identity? Do reporters and editors talk about source diversity routinely? Do reporters have goals or performance metrics around this topic? Remember that those efforts are invisible unless you shine a light on them — overall as a newsroom and within specific stories.

How many people do you interview?

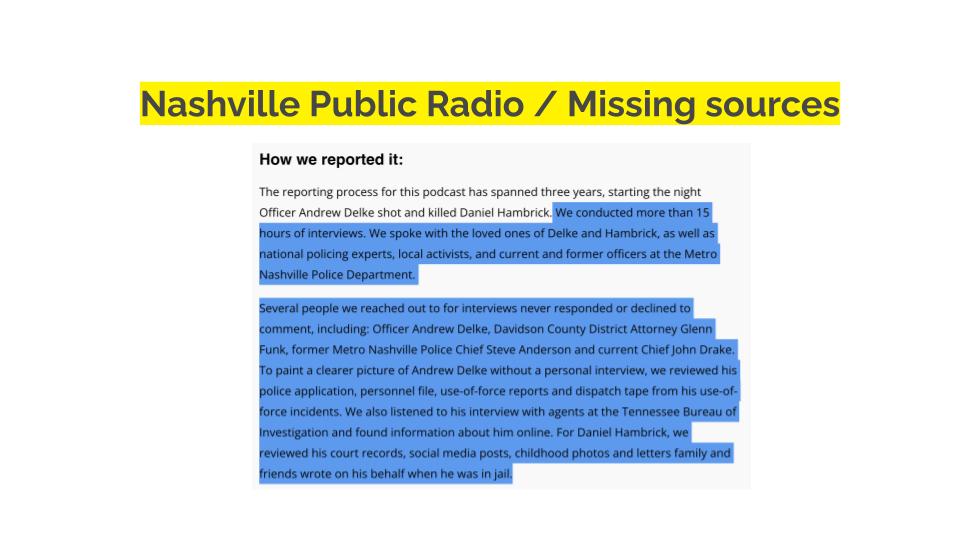

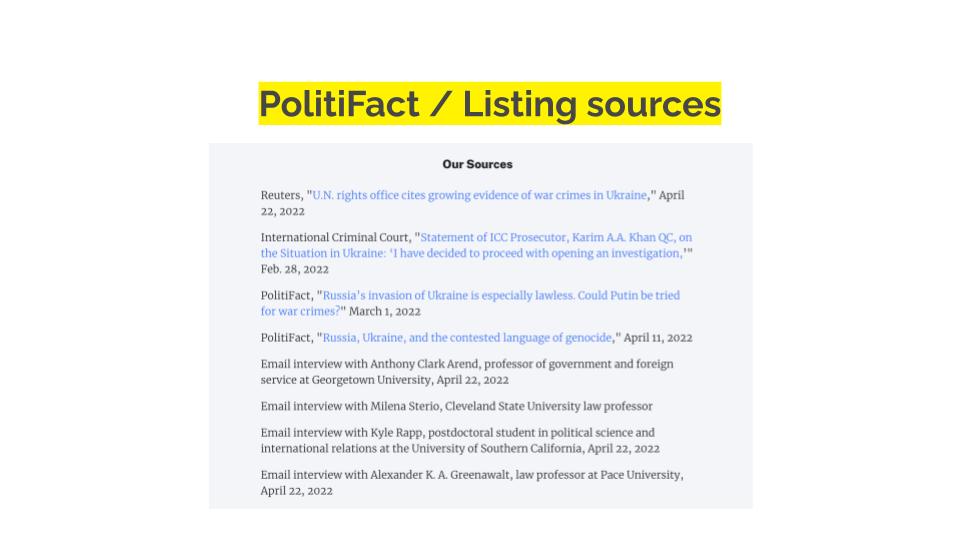

People might not realize how often people who are interviewed end up getting left out of a story. (See the Trust Kit on Earning Trust With Sources for advice on how to communicate clearly with those people.) That’s a typical part of a thorough reporting process, right? Some people give important background but don’t end up being quoted. Sometimes you talk to eight people to make sure you understand a range of views, but you only have room for three in the story. If that’s the case for you, consider acknowledging it. You could use language like:

“For this reporting, I also spoke with other sources who are not quoted in the story. Through conversations with them, I was able to gain insight into the topic and more importantly gain a better understanding of the facts, allowing me to produce a story for you with more context and diverse perspectives. Those people include: ………”

We should also be more transparent about the job the sources are doing in the story — and what they do and don’t represent. It’s unhelpful and sometimes dishonest for journalists to say “neighbors in this area feel …” if we only talked to two or three of them. Instead say, “the two neighbors we talked to about this said …”

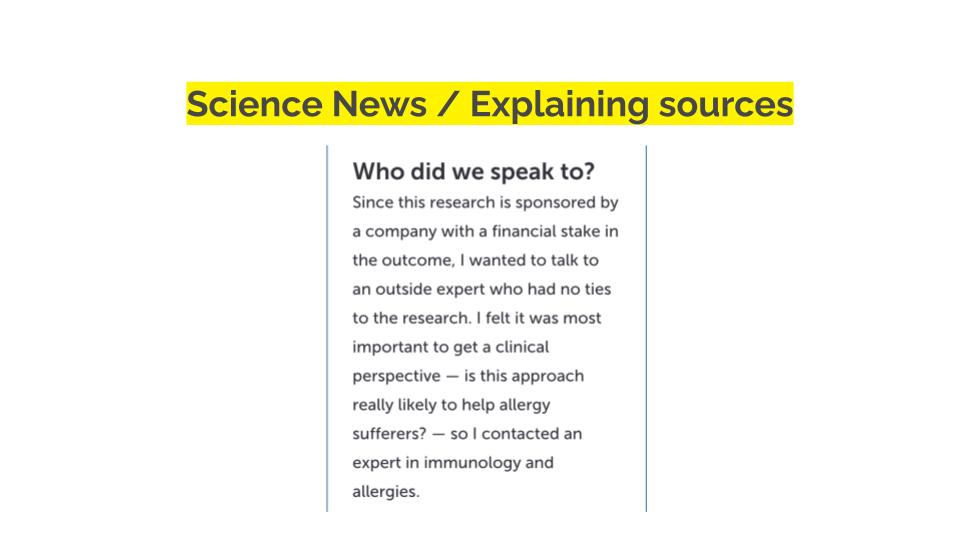

How do you make sure your sources don’t have conflicts of interest or hidden agendas?

It is standard practice for journalists to investigate sources’ relationship to people and organizations they are speaking about. Are they financially invested in the startup they’re praising? Do they have family who work at the nonprofit they’re raising attention for? Do they have personal or financial connections to the accused public official they’re defending? Journalists don’t always catch it, but we attempt to check. Remember that the public won’t automatically know those issues are an important part of our integrity.

Does your newsroom have standard questions reporters ask sources to ensure there’s no conflict of interest around a story? Or questions that an editor asks a reporter to make sure there’s no complicating relationship between the reporter and who they interviewed? Even if it’s not an official policy, can you share your approach for specific stories?

How do you work to be fair to sources, and what if you don’t hear back from them?

If your story will make statements or accusations about someone, will you give them the chance to respond? If so, does that mean you will give them sufficient notice? (We all know there are times a journalist says in a story that someone “did not get back to us before deadline,” when in fact the person wasn’t asked to comment until 30 minutes before a story went live.)

If you are unable to reach or get comment from a key source, it’s best to include a note about that in the story, along with an explanation of what you did to try to balance that missing perspective in the story.

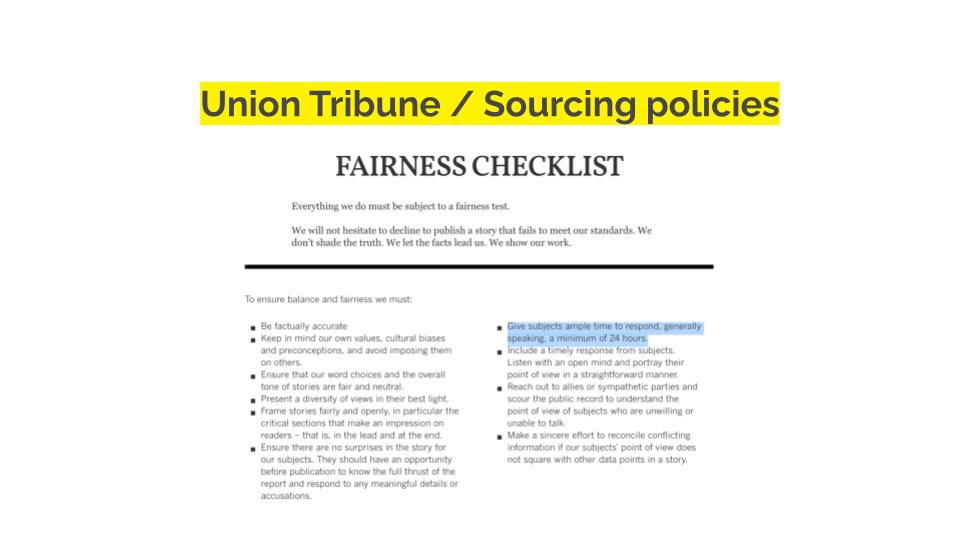

For inspiration, consider these statements from The San Diego Union-Tribune’s Fairness Checklist.

To ensure balance and fairness we must:

- Ensure there are no surprises in the story for our subjects. They should have an opportunity before publication to know the full thrust of the report and respond to any meaningful details or accusations.

- Give subjects ample time to respond, generally speaking, a minimum of 24 hours.

- Include a timely response from subjects. Listen with an open mind and portray their point of view in a straightforward manner.

How would you articulate your own staff’s commitment to treating sources fairly?

What happens if someone doesn’t want their name published? Can they stay anonymous?

The use of anonymous sources is relatively infrequent in most newsrooms, but most people don’t understand the reasons behind the decision to let someone remain unnamed.

Also remember: The word anonymous can contribute to confusion. Some organizations (like RTDNA and the Toronto Star) have begun referring to confidential sources instead. Whatever word you use, be consistent and always include an explanation.

Make sure your newsroom is consistent in your decision-making around letting a source remain unnamed. Don’t have a policy? Start there. And once it’s clearly internally, publish your guidelines. That demonstrates that you make decisions intentionally and consistently. (Otherwise, people assume that you make them based on personal whim or your own agenda.) Newsroom policies should be public whenever possible. And stating clearly your commitment to ethical, responsible sourcing is especially key.

- Here’s how NPR lays out clearly the goals, pitfalls and guidelines behind their soucing decisions.

- The New York Times includes this explanation in a piece on the topic: “Reporters and editors ask themselves: How does the source know this information? What’s the motivation for telling us? Has she or he proved reliable in the past? Are there ways to corroborate the information? Often we explain some of this background in the story, while still taking care to protect the source’s identity.”

The next step is to mention the policy every time it applies. Don’t assume that once you have publicly shared your criteria, your audience will find it, remember it and know when it applies. Users care about the policy governing the use of anonymous sources when they are consuming a story featuring an anonymous source. There are many benefits — and no significant downside, aside from giving journalists one more thing to think about — to linking to or mentioning the policy every single time you let a source go unnamed.

-

- The New York Times includes a box within stories explaining their policy. (Example here.)

- Put it in an editor’s note at the top of the story, as The Michigan Daily did here.

- You can also put the reference in the story itself — in a parenthetical, a clause or a mention on air. “Because of fear that speaking out would lead to dismissal from her job, we have allowed this source to remain unnamed, in accordance with our policy (link).”

- Look for chances to mention it in newsletters or on social media, where you can be more conversational. “This story includes an anonymous source, which is something we seldom do. Learn more about our strict criteria here.”

How do you decide whether to cover polls?

People are often both frustrated by and skeptical of political polls. Frankly, that frustration is natural and skepticism is appropriate in today’s news climate.

Look for chances to educate people about how polls work, how you work to be careful with polling data and how polls fit into political discourse in general.

As journalists, we learn how much credence to give polls. We learn to look for independence in the pollsters (financial and political). We inspect their methodology. But are you explaining any of that? Doing so could build trust in your methods and can also help your audience be more educated consumers of polling data.

Think about creating a page that explains how your organization handles polling data, and linking to it from all stories that reference polls. With all the polls in the field, how do you decide which ones to run stories on? (FiveThirtyEight explains its decisions here.) Which do you not cover and why? What are your benchmarks for credibility and relevance? And if you run your own polls, explain why and how, as The Atlanta Journal-Constitution did here.

Perhaps above all, inject a dose of uncertainty into how you report on polls, as The 19th did here. Resist the temptation to be definitive or oversimplified with your language and characterization.

Can your audience recommend additional sources?

Use your story as an opportunity to ask for feedback on who else the newsroom should be talking to about particular subjects. It can be a great way to reinforce the idea that you rely on community input in general. Consider including a box (or a note at the end of a story, or a mention on air, or a comment on social media, etc.) indicating that it’s important to you to hear from people with a range of perspectives on the topic and inviting folks to get in touch with suggestions.

Going public

Ready to start talking with your audience about sourcing? Great! Once you’ve answered some of the above questions, it’s time to go public. Here are some options for how you can format them and share your sourcing decisions publicly.

- In a box: A simple and popular option is to put a pull-out box next to or below a text story (online or in print). It’s usually quick for newsrooms to create. And in research we’ve done with the Center for Media Engagement, we found strong evidence that including a box with transparency language does help increase trust.

- With an on-air story: During an on-air segment, you can simply add a sentence or two explaining why it is you are airing an interview with a specific individual. Here’s an example of how station 3 New Now did this.

- In a note above the story: An editor’s note at the top of a story can be a good, quick way to point to how you’re working to be fair and consistent with your coverage.

- Within the text of a story: It’s not as awkward as you might think to add this information directly into a story, or link to a policy.

- In a newsletter: Simply add a sentence or two to the top of your newsletter or when you’re promoting a story on your website.

- In a social post: Whether you’re posting from your personal account or from an organization’s brand account, use the social chatter to share more about your sourcing decisions.

See how other newsrooms do it

For some inspiration, here are some examples of how newsrooms are talking publicly about their sourcing. For more newsroom examples, check our our newsroom example database.

We’re here to help!

Congratulations on getting this far in the Trust Kit! 🎉 We know taking the steps to earn trust isn’t always simple or easy. It takes time and often requires a shift in newsroom routines or workflows.

Any progress you make on implementing strategies in this Trust Kit should be celebrated as a win!