We set out to better understand how can newsrooms be transparent about their use of AI and not lose trust — maybe even build trust? Here’s what we found.

New research: How AI disclosures in news help — and also hurt — trust with audiences

News consumers are skeptical, uncomfortable and worried about AI, and many people bring those feelings into how they view its use in journalism. This is a broad but striking takeaway from new research from Trusting News.

In this study, news consumers came across AI use disclosures in real news stories and were asked, among other questions, to share their feelings on the disclosure language, on the general use of AI in news and on how the AI use affected their trust in the content.

The research, which consisted of survey data and two A/B testing experiments, involved 10 newsrooms in the U.S., Brazil and Switzerland. It was conducted with Dr. Benjamin Toff, the Director of the Minnesota Journalism Center at the University of Minnesota and was supported by a grant from the Patrick J. McGovern Foundation.

Trusting News focuses on solutions for newsrooms to build trust with their audiences, and finding solutions was the goal behind this newsroom research cohort. Trusting News wanted to learn: How can newsrooms be transparent about their use of AI and not lose trust — maybe even build trust? The question also guided previous research from Trusting News, which showed that 94% of people want journalists to be transparent about their use of AI.

After analyzing this most recent research data, Trusting News has some updated answers, recommendations and solutions for journalists to answer that question. The recommendations are in an AI Trust Kit, as well as below.

Given some strong negative feelings the research revealed about AI use in news, it’s important to highlight and pause on some key data points.

- There is a majority consensus on how news organizations should approach AI. More than 60% of survey respondents said news organizations “should only use AI if they establish clear ethical guidelines and policies around its use.” But 30% said AI should “never be used under any circumstances.”

- The disclosure of AI use generally led to a decrease in trust in the specific news story. Survey respondents who reacted to AI use disclosures in real news stories that cohort newsrooms published were especially likely to express distrust. In A/B testing of similar disclosures, people elicited similar decreases in trust when seeing that AI was used; however, the type of AI use and how these uses were framed in real-world stories may influence the intensity of some reactions.

- The reaction to learning AI was used tended to be stronger than any reassurance provided by detailed disclosure language. People were more affected by knowing AI was used than they were reassured by explanations focused on why it was used, how it was used and if humans were involved to check for accuracy and ethics. This finding, along with the others, will be examined more closely in this research post.

These results may not be surprising if you consider other research related to trust and AI generally, not focused only on news. According to the 2025 Edelman Trust Barometer, less than a third (32%) of Americans say they trust AI.

This context is important as journalists and the news industry decide how to move forward. Ultimately, there is a lot that AI and technology can do to help make news coverage more useful and accessible to audiences. But newsroom decisions should be made based on a deep understanding of how the public perceives the emerging technology, and news organizations must be considerate of how significant portions of their own audiences intensely distrust any use of these technologies.

This research should not deter journalists from using AI but rather should lead to discussion and careful decision-making about how AI is used, how it’s disclosed and explained, and how journalists are working to make sure audiences are comfortable with (or at least understanding of) their use of AI.

This research doesn’t give us all the answers, but it does offer helpful insight into some key questions that can guide newsrooms as they navigate how to use AI ethically and responsibly while communicating with audiences about it, including:

- How does disclosing AI use affect trust?

- How do audiences respond to different types of AI use in news content?

- If disclosing AI use can negatively affect trust in news content, should journalists avoid disclosing?

- Does it matter how an AI use disclosure is written?

- Does it matter where and how an AI use disclosure is placed?

- Do the answers to these questions vary with different types of news consumers?

Want to learn how to build trust while using AI? The AI Trust Kit has suggested language for AI use disclosures, worksheets to assist in writing AI use policies/disclosures, examples of how newsrooms are being transparent about their AI use, audience feedback/survey tools and more.

How does AI use disclosure in news affect trust?

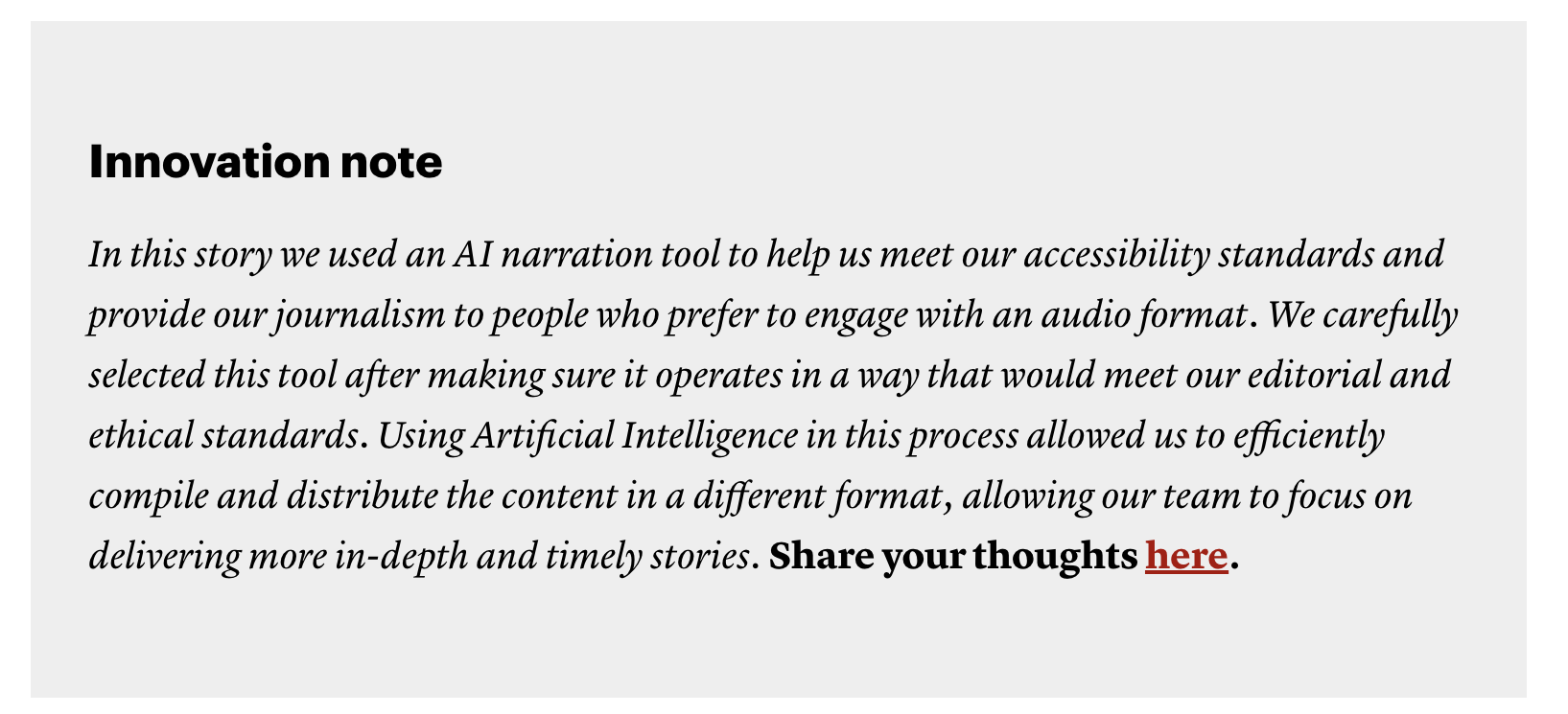

The 10 newsrooms participating in the Trusting News research were selected because they wanted to experiment with how they write and display AI use disclosures in their news content. To participate, newsrooms had to be regularly using AI. The specific use cases varied, ranging from story summary and editing assistance to coding assistance, story translation and podcast creation.

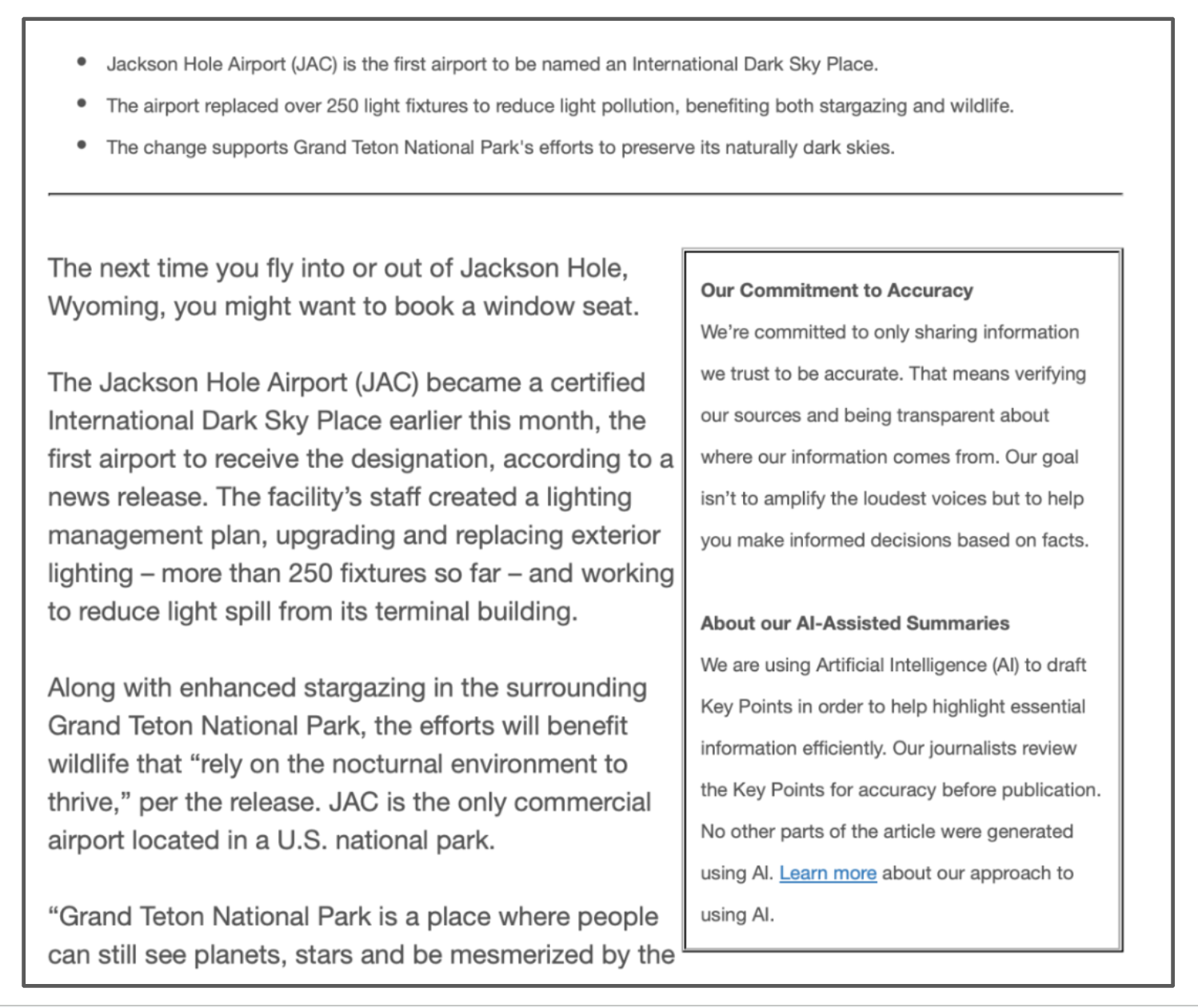

Once the experimentation started, newsrooms wrote personalized AI use disclosures for stories where AI was used. Trusting News provided newsrooms with an AI disclosure template and sample language to consider using. The disclosures written by newsrooms varied in length, style and in-story placement, but each was informed by guidelines provided by Trusting News that suggested including details about how AI was used, what human oversight the newsroom maintained and why the tools were being used.

At the end of the disclosure language, the newsrooms included language inviting news consumers to take a survey about its AI use, the disclosure and how learning that AI was used made them feel about the news content. In every case, newsrooms always had a journalist review the AI-assisted content before publication, and most disclosures made sure to include that information.

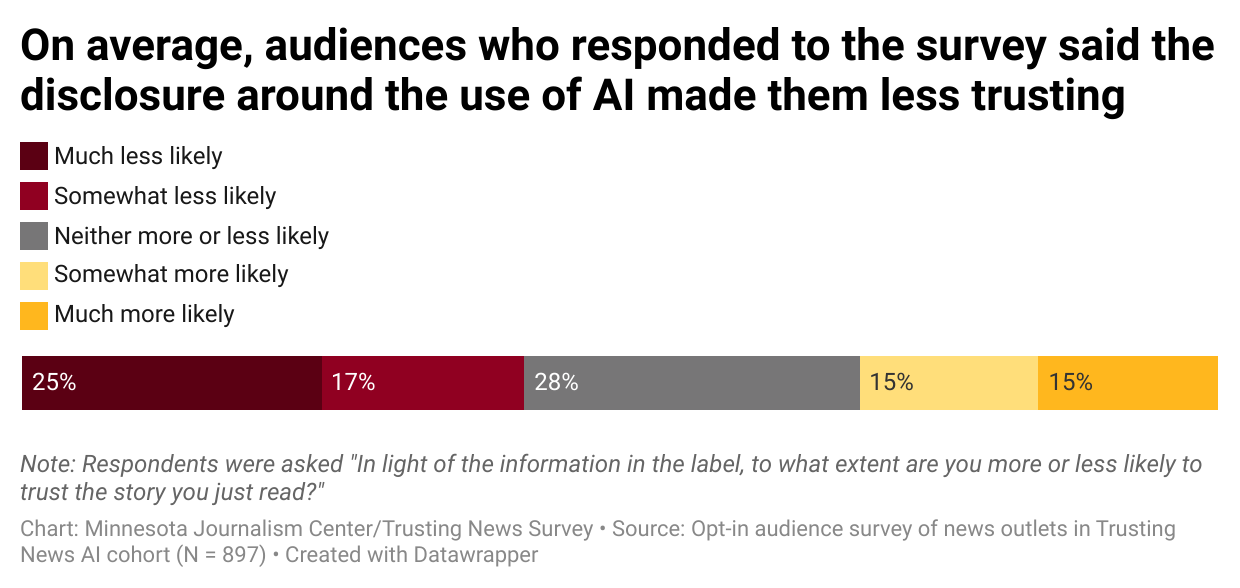

News consumers who saw an AI use disclosure in these real news stories were asked, “In light of the information in the label, to what extent are you more or less likely to trust the story you just read?”

The disclosure generally led to a decrease in trust in the specific news story, with more people (42% of respondents) saying they were “less likely” to trust the story after seeing the disclosure. Less than a third (30% of respondents) said they felt “more likely” to trust the story.

Depending on who the news consumer was, there were some differences in how they responded to seeing that AI was used in the news story. For instance:

- Younger respondents (people under 35 years old) were more likely to report being “much less likely” to trust the story (31% of respondents) compared to older age groups (20% for people 55 years or over).

- Respondents who already distrusted news media in general were more likely to report a negative impact on trust from AI use labels.

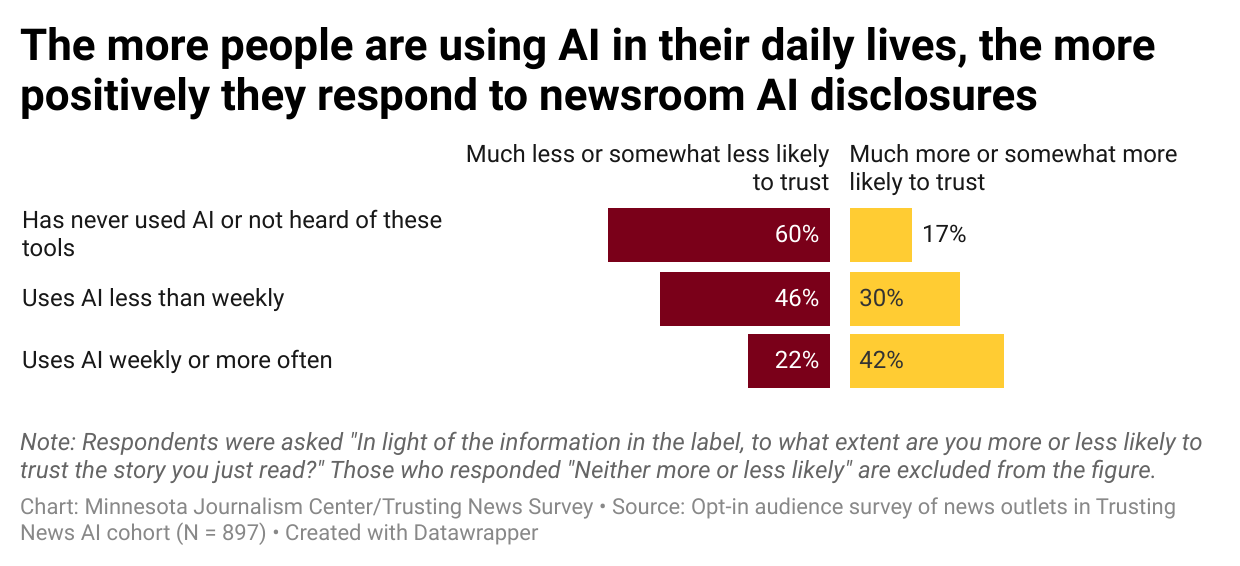

- Respondents who use AI more in their daily lives had a more positive response to newsroom AI use disclosures. More than 40% of those who reported using AI “weekly or more” said they were “much more” or “somewhat more likely” to trust the story after seeing the disclosure. This was true even though younger respondents were also more likely to say the disclosures made them less likely to trust the story.

When survey respondents were asked how news organizations should approach AI, the vast majority said they thought news organizations should only use AI if they first established clear ethical guidelines and policies around its use.

On the other hand, 30% said they thought news organizations should “never use AI under any circumstances.” This is a larger percentage than was found in an earlier representative survey of Americans conducted by the Poynter Institute. The difference isn’t surprising, given this latest research from Trusting News involved newsrooms’ actual audiences, people who are typically more engaged news consumers and, as we show below, also among the most skeptical of AI.

How do audiences respond to different types of AI use in news content?

In addition to survey work with newsrooms’ real stories, Trusting News and Toff conducted two separate rounds of A/B testing involving a total of five distinct AI use cases.

In the first experiment, the AI use cases included:

- AI-assistant transcription from interviews

- AI-assisted document analysis in enterprise stories

- Using generative AI to create a first draft of a story, later revised and edited by a human

In the second experiment, the AI use cases included:

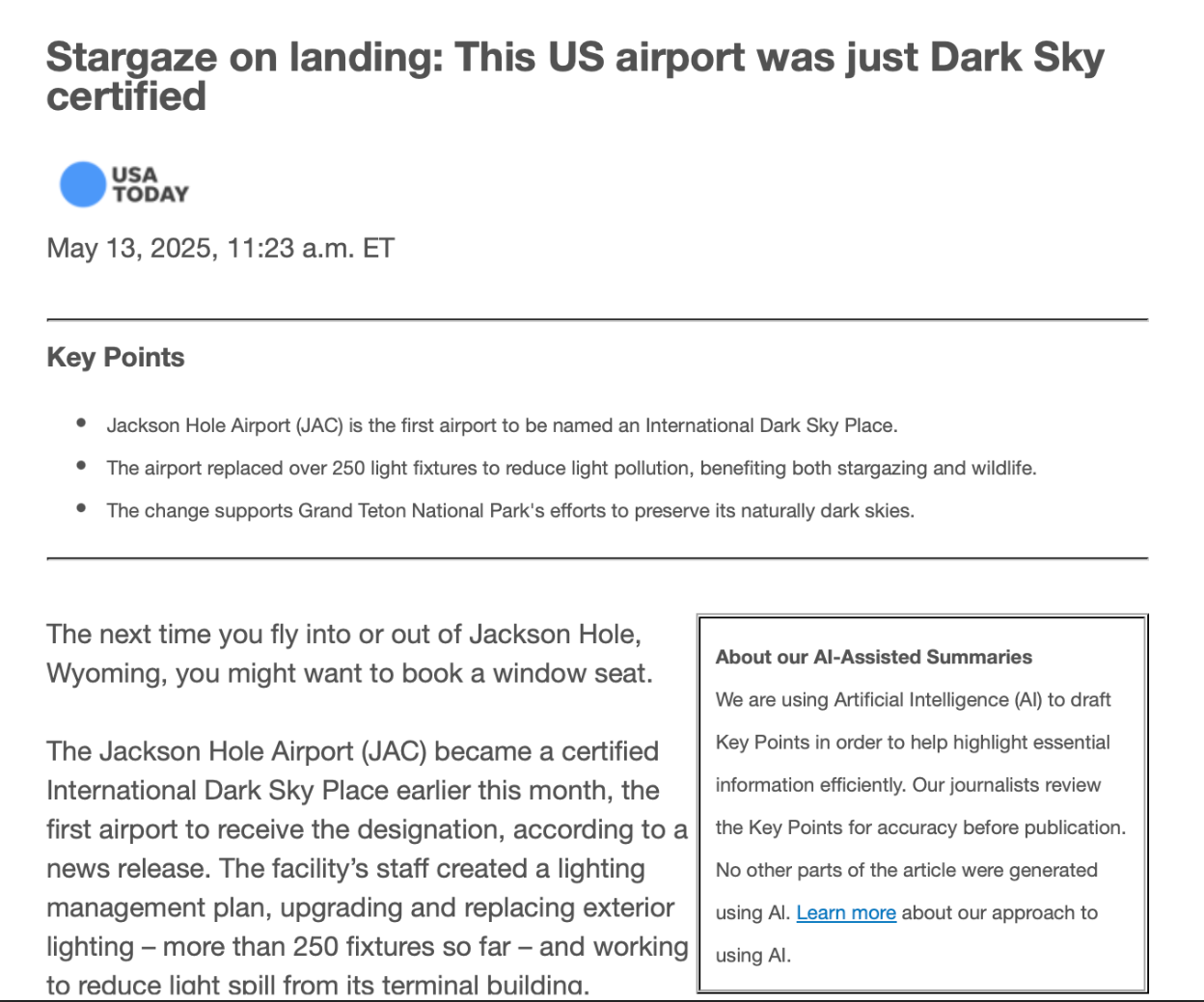

- AI-assisted story summaries

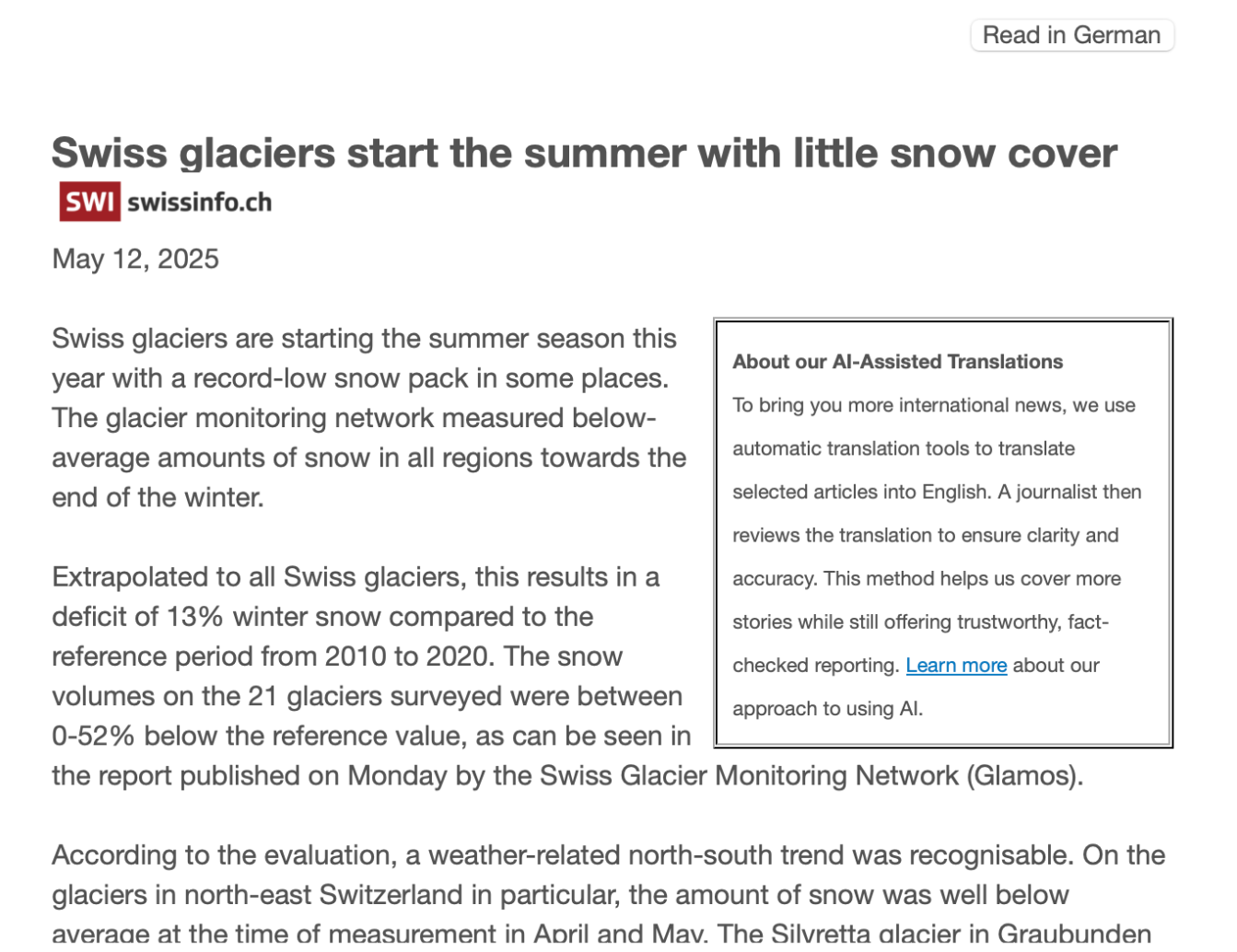

- AI-assisted story translations

This testing was conducted in a controlled environment through a web-based survey platform using a quasi-representative sample of Americans and not with newsroom partners’ actual audiences.

In the A/B tests, which compared how people reacted to stories when they saw disclosures about the use of AI versus people who read the same stories without disclosures, we found, on average, similar decreases in trust for some AI use cases, but not all.

In the first experiment, respondents who saw disclosures about using AI to analyze documents or transcribe interviews were less likely to find the news organization trustworthy by a small but statistically significant margin. We also found decreases in trust associated with disclosures around using AI to draft stories (in the first experiment) and AI-assisted story summaries (in the second experiment), although the average difference in trustworthiness was not statistically significant for either of these use cases. AI-assisted translation was associated with virtually no differences in perceived trustworthiness.

One possible conclusion is that people are more comfortable with some types of AI use than with others, which has been shown in previous research from us and others.

It is worth noting, however, that the two experiments, and the survey we conducted with newsroom audiences, are not entirely comparable. There are several reasons why we think the last two use cases examined in the second experiment were not associated with the more substantial decreases in trust we found in the first experiment and in the survey. These include:

- Differences in the samples. Survey responses to AI disclosures on the websites of the newsrooms participating in the Trusting News cohort involved a non-representative sample of audiences who took the time to fill out a survey and offer their feedback. It is likely that many of those who did so felt particularly strongly about AI compared to even average news consumers. The two A/B experiments allowed us to assess reactions across a more representative cross-section of the public.

- The two specific AI use cases in Experiment 2 may have been perceived as more benign. AI-assisted language translation (Translation) and AI-assisted story summaries (Key points summary) were the only two use cases in the second round of A/B testing. They were specifically selected because they were seen as the most common current use cases in news by the 10 newsrooms in the research cohort. Translation and story summary were also two use cases the newsrooms were most interested in exploring more moving forward.

- The names of the brands were shown in Experiment 2, but not in Experiment 1. The stories in the second round of A/B testing were drawn from actual articles involving two news brands in the Trusting News cohort: Swiss Info and USA TODAY. In Experiment 2, respondents saw the news brand corresponding to each of these stories, whereas in Experiment 1, the stories were attributed to a generic, nonexistent news organization, so comparisons between the treatment and control groups were more abstract.

- Disclosure language was consistent in Experiment 2, although how disclosures appeared varied. All respondents in the second A/B experiment who saw AI disclosures were provided the same detailed disclosure, whereas in the first experiment, the level of detail provided was randomly varied (more on that below). In the second experiment, we instead varied the placement and display of the disclosure, which, as we show below, had an impact on whether or not people noticed it. In the survey that cohort newsrooms shared with their audiences, the AI use disclosures seen by survey respondents varied as newsrooms customized recommended language from Trusting News and made changes to see how news consumers would respond.

- Disclosure language included a link to AI policies in Experiment 2. While the language in the A/B testing disclosures was consistent and closely reflected the language used by Swiss Info and USA TODAY for those same use cases, Trusting News and Toff decided to include a link to both organizations’ AI use policies in the disclosure language. While some newsrooms did this in disclosures used in the survey research, many did not. None of the disclosures in Experiment 1 included this additional link since the news organization used in this round of A/B testing did not exist in the real world.

Based on these differences, it is difficult to pinpoint the precise conclusions to draw, but we have several suggestions:

- Including a link to an AI ethics policy might improve trust and confidence in AI use by journalists.

- Responses to AI use from known organizations with established AI ethics policies might be less negative than disclosures about using AI from unknown news organizations. At the same time, as we show below, there are important differences among audiences in how they feel about news organizations using AI. Some of the most engaged news consumers are also the most distrusting of news organizations using these tools — regardless of how detailed a disclosure is provided.

- Placement and display of an AI use disclosure may have a greater impact than the language used in the disclosure. For example, providing an AI use disclosure that has to be clicked on may provide a happy medium for news consumers. Journalists are providing the disclosure people want, but not attracting unwanted attention that may result in general fears and negative feelings about AI being projected on the news content and the newsroom. (More on how placement/display may impact trust in the news content.)

If disclosing AI use can negatively affect trust in news content, should journalists avoid disclosing?

No. Instead, journalists should keep experimenting with options as AI use in news and audience understanding of AI continue to evolve. While it’s true the newsroom surveys show a majority of people trusted a specific news story less when they saw a disclosure, the A/B testing paints a slightly more nuanced picture. And don’t forget, people still overwhelmingly say they want AI use by journalists to be disclosed.

The previous research from Trusting News on this matter could not be clearer, with 94% of people saying they want transparency around a newsroom’s AI use. In that research, they specifically said they wanted to know:

- Why journalists decided to use AI in the reporting process (87.2% said this would be important)

- How journalists will work to be ethical and accurate with their use of AI (94.2% said this would be important)

- If/how a human was involved in the process and reviewed content before it was published (91.5% said this would be very important)

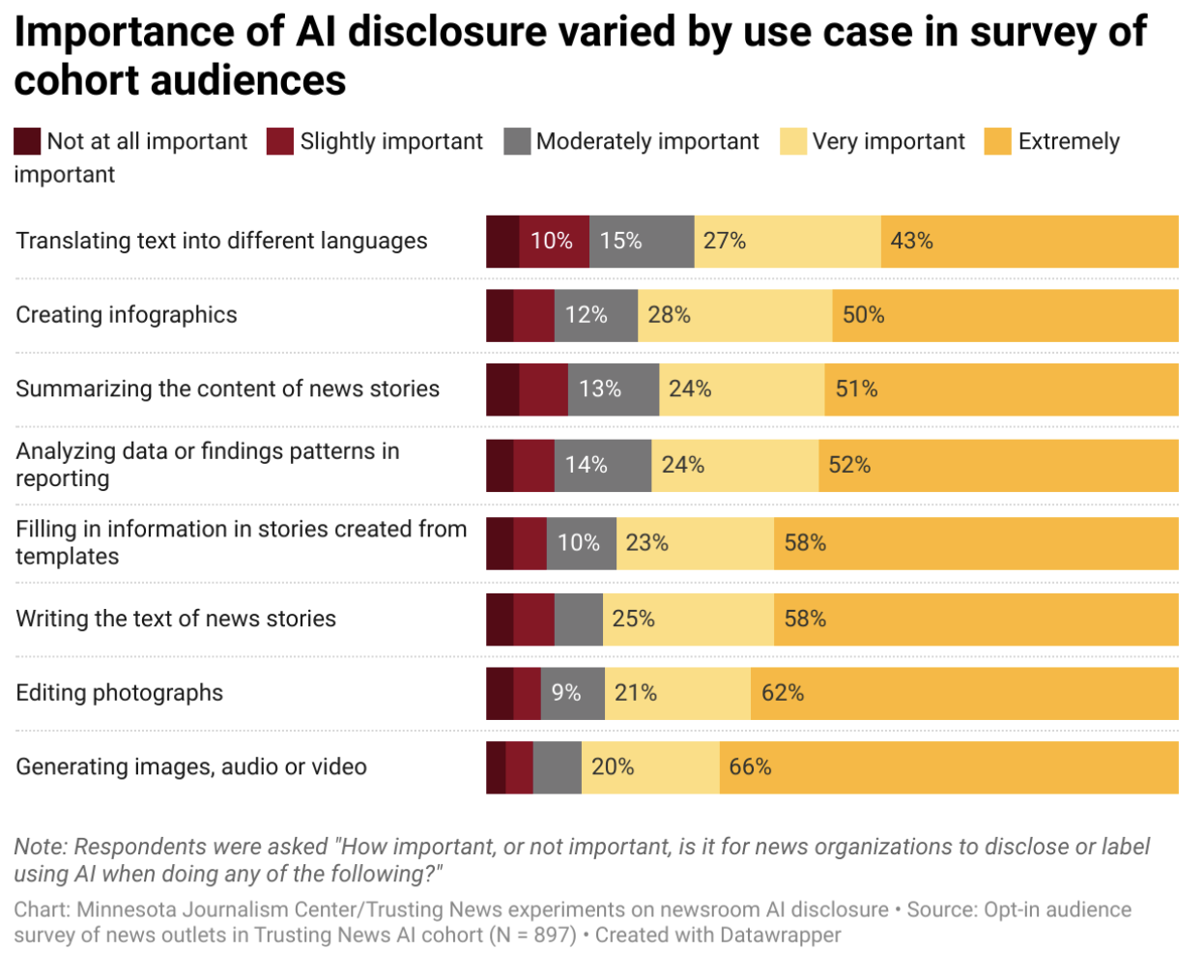

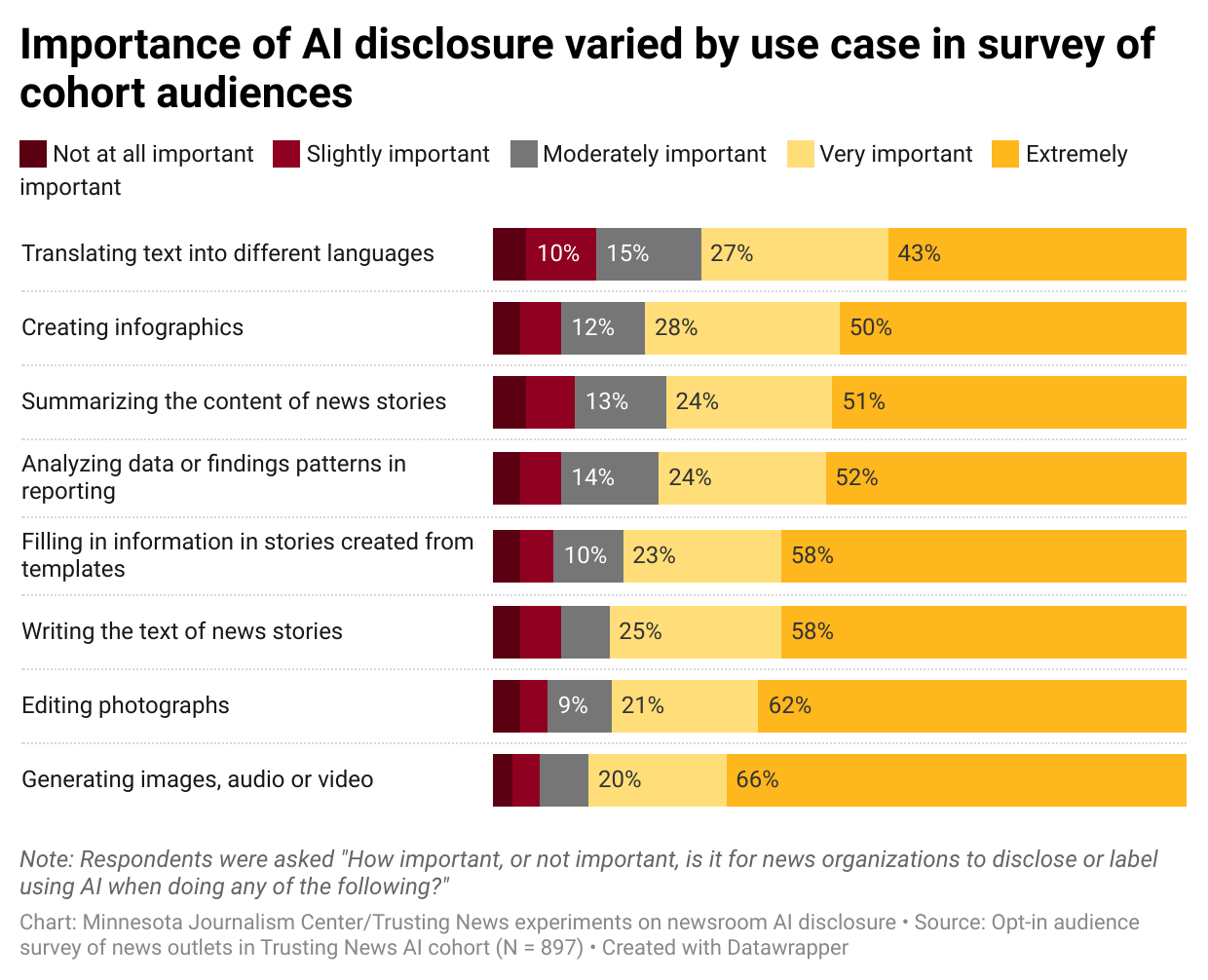

In this latest research, when survey respondents were asked when disclosure of AI use would be important, there was just one use case where more than 50% of respondents did NOT say disclosing that use of AI would be “extremely important.” That use case was translating text into different languages. But even for that use case, 43% of survey respondents still said disclosure would be “extremely important.”

This demonstrates a clear demand for transparency from news consumers. Because the message from news consumers is clear and an analysis of the most widely used journalism ethics codes would support transparency of AI use in news, the answer to the question of whether or not to disclose is: Yes, journalists should disclose their use of AI.

Transparency is a core part of journalism ethics, and people don’t want to be tricked or left in the dark. While this research might tempt journalists to use AI and hope people don’t notice or inquire about it, journalists should instead lean toward transparency in their AI use.

Does it matter how an AI use disclosure is written?

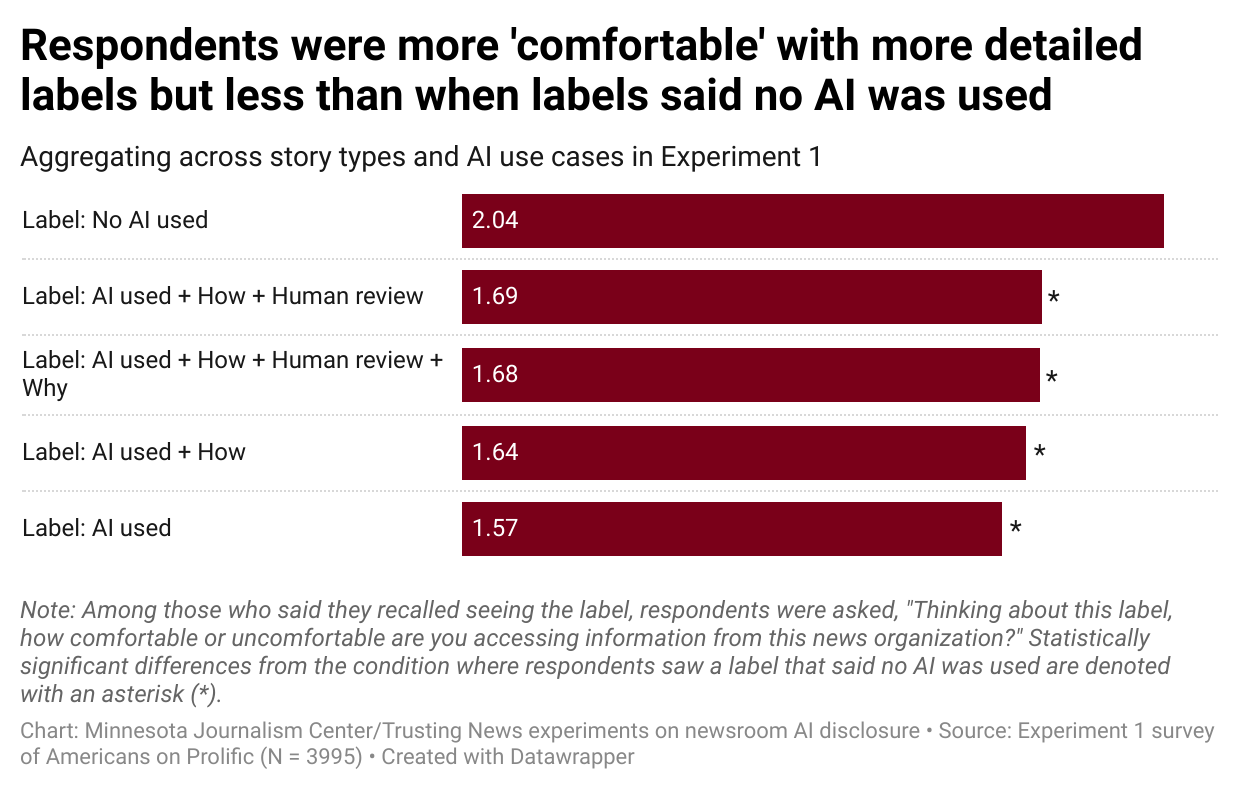

Yes, this research shows that how the disclosure is written could make a difference when it comes to people’s comfort level with the disclosure and confidence in the news organization. While we generally found disclosure around using AI tends to make audiences at least somewhat uncomfortable, if not downright distrusting, providing more information in the disclosure generally had a reassuring effect.

The survey respondents who saw the AI use disclosures in real news stories had a more positive than negative feeling about the information provided in the AI labels. On average, across the disclosures audiences saw, almost 50% of all respondents expressed positive sentiment about the information in the disclosure (30% “Very positive” and 17% “Somewhat positive”) while 32% expressed negative sentiment (18% “Very negative” and 14% “Somewhat negative”). That said, there were considerable differences across organizations, which disclosed using AI for different purposes.

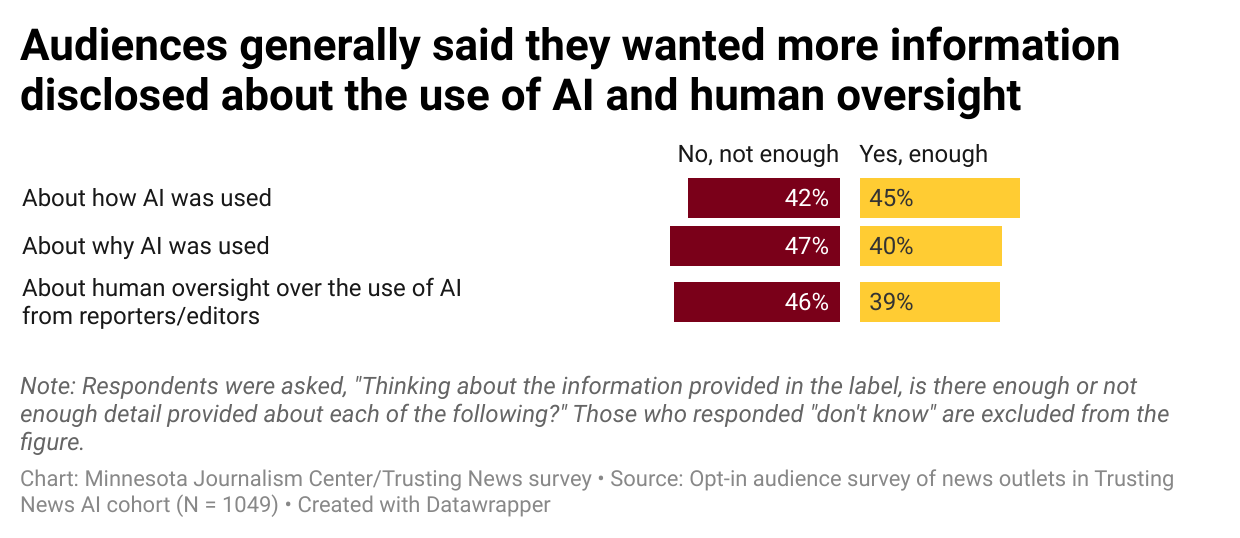

A notable finding is the desire for more detailed information regarding AI use in news in the disclosures — even beyond the level of detail already provided by participating cohort newsrooms. Specifically, people said they wanted more information about “how” and “why” AI was used and about “human oversight” over the use of AI. The graph below details these findings.

In addition, Trusting News was able to get more information on this question through the first A/B experiment we conducted, in which people were provided different versions of disclosure language. The disclosures were varied by how much information they contained and what questions they answered about the AI use. In this A/B testing experiment, the disclosure options included:

- Control: no label/disclosure

- Disclosure/Label: No AI used

- Disclosure/Label: AI was used

- Disclosure/Label: AI was used + how

- Disclosure/Label: AI was used + how + human review language

- Disclosure/Label: AI was used + how + human review language + why

The graphs below show that when a respondent saw an AI use disclosure, their confidence in the news organization and comfort level with the label increased the more information the label included. More detail led to more trust.

When there wasn’t a label (the control) or the label said that no AI was used, respondents showed the highest confidence in the organization. Similarly, among those who saw a label, respondents were significantly less comfortable with labels that disclosed AI use compared to labels that stated that no AI was used.

Does it matter where and how an AI use disclosure is placed?

Yes, where an AI use disclosure is placed matters. In the second controlled A/B testing we conducted, people were more likely to notice disclosures placed at the bottom of the article or in the sidebar of the story page. The percentage who said they noticed the disclosures when positioned in these places exceeded 80%.

In contrast, labels that only appeared when users hovered over them were more likely to be missed, especially in the translation use case, where only 26% of people noticed the label. On average, less than half (44% of respondents) saw the hover labels. When that is compared to the average noticeability for all labels, almost two-thirds (which was 74% of respondents), the data show people are much less likely to see a disclosure if they have to interact with it to view it.

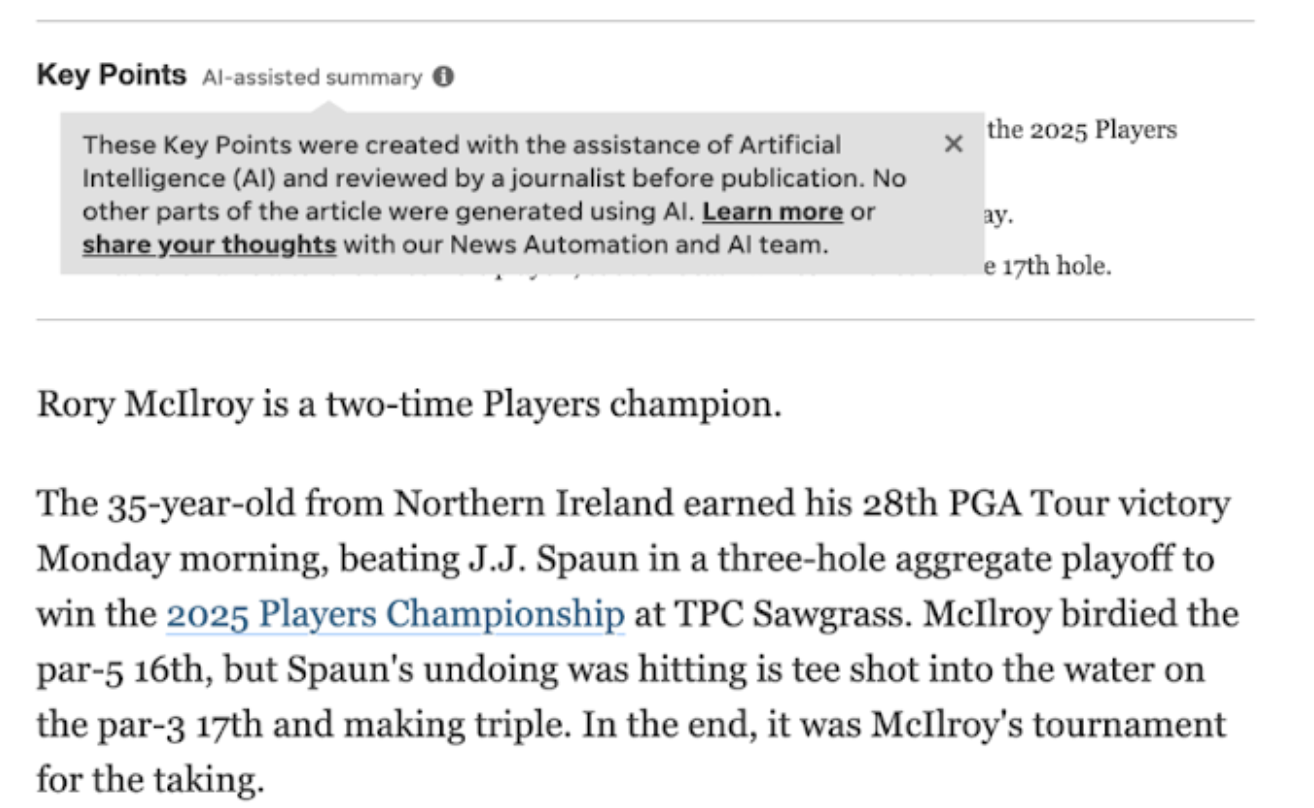

Trusting News and Toff tested hover labels because it was a use case being implemented by newsrooms inside and outside the research cohort. For example, USA TODAY’s AI use disclosure for its “Key Points” story summaries includes an “AI-assisted summary” label with a clickable “i” icon. When news consumers hovered over the icon, the disclosure appeared.

In addition to placement, our first round of A/B testing also shows news consumers are more likely to see an AI disclosure the longer it is. People reported being most likely to see a disclosure if it contained information that AI was used, how AI was used, why AI was used and that a human reviewed it. When the label just disclosed that AI was used, the news consumer was less likely to notice it.

Do the answers to these questions vary with different types of news consumers?

In the research we conducted, there were differences among news consumers in how they responded to seeing that AI was used, their comfort with AI-use disclosures and their general thoughts on how journalists should use AI.

Overall, the sample of people who responded to our audience survey about disclosures tended to differ from the public at large. They tended to be older (43% were 55+), whiter (92%), and very well educated (41% held a bachelor’s degree and an additional 39% had a master’s or doctoral degree).

While the largest proportion of respondents said they used generative AI tools themselves either weekly or every day (40%), a third of the sample said they had “never” used AI tools before. These rates are comparable to the Poynter/MJC representative survey data on this question for more educated segments of the public. Furthermore, nearly half (48%) said they had heard only “a little” or “nothing at all” about the use of AI in the production or distribution of news.

When it comes to what the survey results showed about how different people responded to the use of AI, some differences worth highlighting include:

- People under 55 years old were more likely to feel “Very negative” about AI use disclosures compared to those 55 years or older, even though younger people were more likely to use AI on at least a weekly basis than older people.

- The youngest respondents (those under 35 years old) were also more likely to report being “Much less likely” to trust the story after seeing AI was used, compared to older age groups.

- Respondents who said they trusted news media in general reported feeling more positive about the disclosure than those who reported more distrust in news.

- Respondents who said they distrusted news media in general were more likely to report feeling negatively about the organization after seeing the AI disclosure.

- Despite the fact that younger audiences tended to react more negatively to disclosures, the more frequently audiences said they themselves used AI tools and the more knowledgeable they said they were about generative AI, the more they tended to react positively to disclosures.

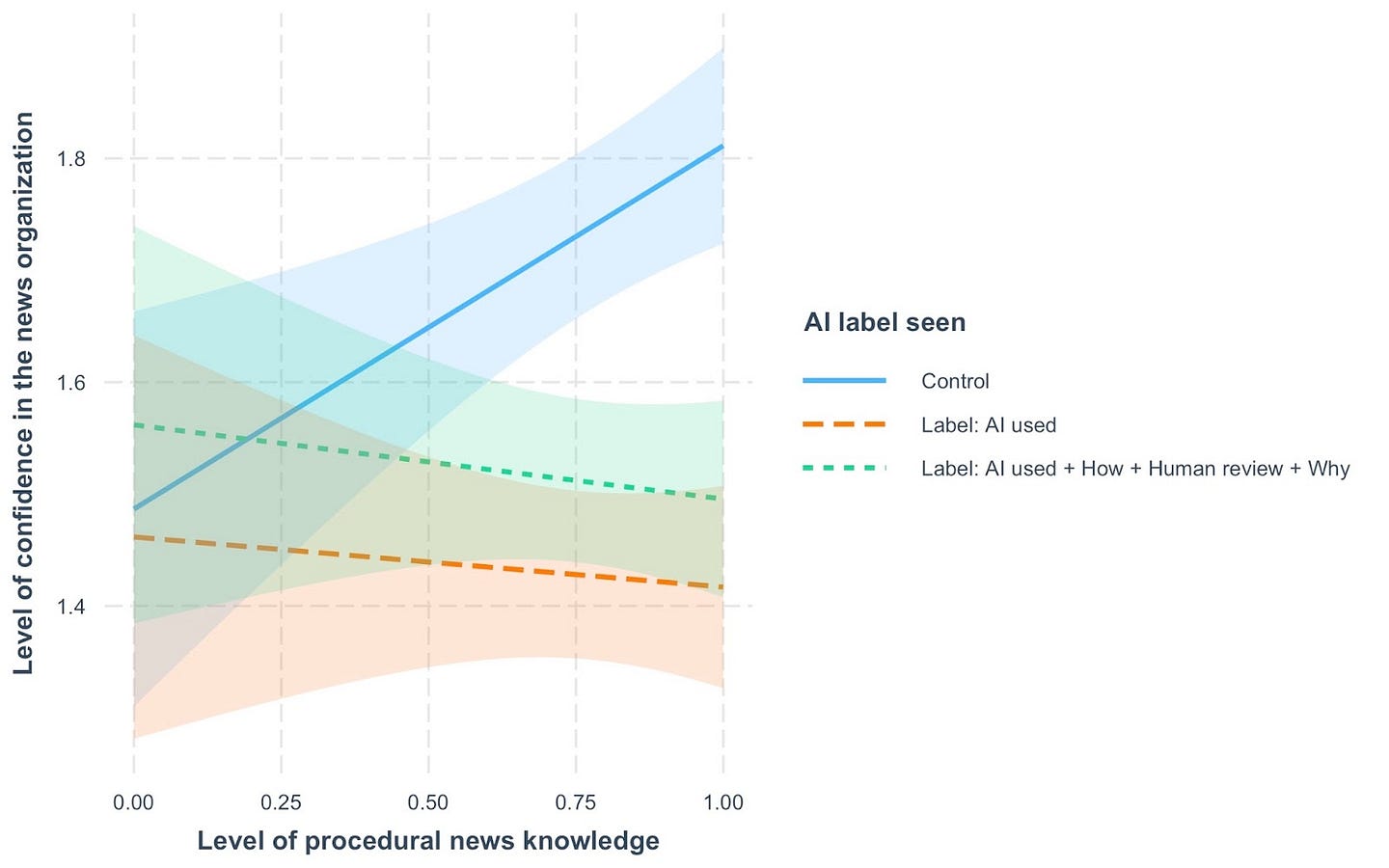

In the first A/B experiment, in which people were provided different versions of AI use disclosure language, Trusting News was able to get some data examining the relationship between the impact of disclosure and what is called “procedural news knowledge,” or what audiences know about how journalism is made, as well as levels of trust in news in general. This additional data allowed us to examine systematic differences in patterns of responses among different audience subgroups.

In future write-ups of this research, we plan to describe these results in more detail, but here we highlight two specific findings about audience differences.

First, people who know more about how journalism is made typically express the most confidence in news organizations. In the graph below, you see this shown in the control condition where no AI disclosure label was included.

However, this type of respondent appears most impacted by seeing an AI use disclosure. Holding all other differences constant, when this group of people saw labels about the use of AI, on average, they expressed the lowest confidence in the organization. At the same time, we also see that the negative effect associated with AI disclosure is reduced for this group of people when the disclosure included more information beyond simply that AI was used (how it was used, how human review was maintained, and why the organization had opted to use AI).

On the other hand, among people who are less familiar with how journalism is produced, seeing the AI disclosure label did not lead to any statistically significant changes in their confidence toward the news organization. In other words, the skepticism we see associated with disclosure about the use of AI is driven primarily by those who are most knowledgeable about how journalism works.

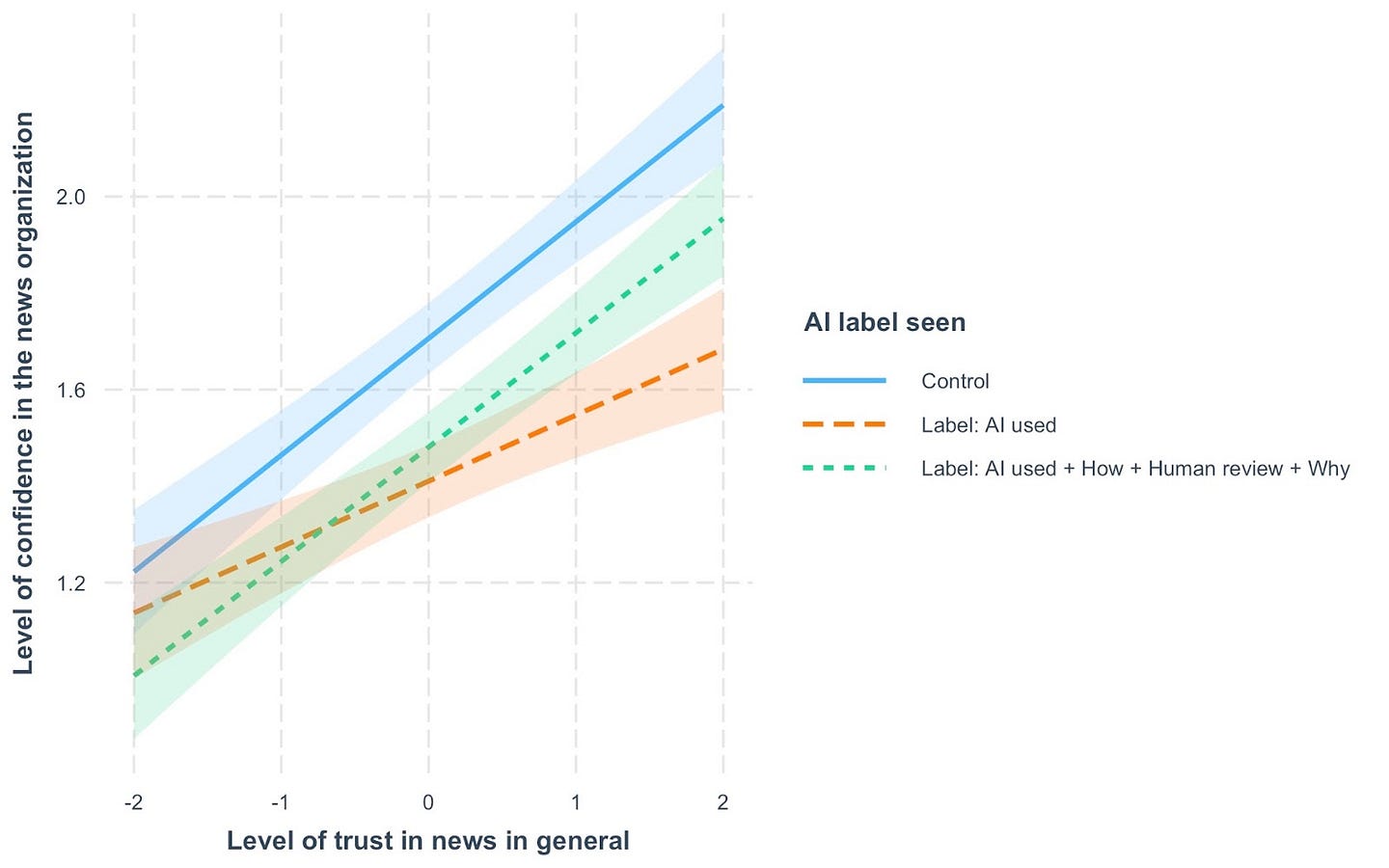

When we look at the relationship between trust in news in general and responses to the inclusion of labels on stories disclosing the use of AI, we find a somewhat more uniform pattern. Disclosure is associated with reductions in confidence across the board, although the decreases are largest among those who otherwise say they are most trusting toward news.

The degree to which more detailed information in the disclosures mitigated the negative impact of the labels was largely concentrated among those who otherwise said they trusted news in general. Among those who said they did not trust news, levels of confidence in the organization were low and at indistinguishably low levels for all respondents, regardless of which version of AI disclosure they might have seen.

In short, the more detailed disclosures appear most effective among those who are otherwise most trusting of news, and it is this same group whose levels of confidence appear most vulnerable to distrust when AI use is disclosed.

Trusting News recommendations

While there’s no one-size-fits-all solution, this research points to ways journalists can be more transparent, thoughtful and responsive as they experiment with AI use in news content. Despite the skepticism, concerns and fears audiences have about AI, here are some steps journalists can take to help make AI use more understandable and acceptable to their news consumers. Read more about all of them, and see examples, in our AI Trust Kit

- Listening and engaging with your audience on AI use is a must. Don’t assume how people feel. Ask them. Talk to them. Because attitudes vary widely and are changing rapidly. In this research, we saw a significant portion of news consumers say they don’t think newsrooms should use AI for any reason. Journalists cannot expect their audiences will just accept their well-intentioned use of these tools. This, though, could change. Over time people could become more accepting of AI use in news. But the only way we will find out is by listening and engaging in a two-way conversation with our communities. (Resources on engagement.)

- Disclosure is essential. People overwhelmingly want AI use disclosed — and when given the information they say they want, they still want more. Journalists must disclose their use of AI. (Resources on how to disclose.)

- In-story disclosures are not enough. At this point in time, it seems that seeing a detailed AI use disclosure may not be enough to gain user trust with the use of AI. For some audiences, any association with using AI is viewed as a red flag, and many are still learning about what these tools can do and what they can’t do. Journalists need to consider further explanations with behind-the-scenes explainers and AI literacy initiatives. Journalists should also examine how they are covering AI in news stories. If coverage of AI focuses on potential dangers, but then we use the tools ourselves, why would we expect people to automatically trust our own AI use? We should continue to be critical and focus on accountability, but unless we’re also offering explanations and responsible uses cases, are we really providing complete context and fair coverage? (The Trusting News team will focus on these topics next in our work with journalists and researchers. Sign up to learn alongside us, and apply to join a cohort here. )

- Emphasize commitment to accuracy/ethics, and have an AI use policy. All newsrooms should get on the record about how they are (or are not) using AI. In addition, when disclosing AI use in individual stories and news content, newsrooms must explain how the content can still be trusted to be accurate and ethical. (Resource on policies.)

- Emphasize the human elements of journalism. News consumers, especially the most engaged and loyal news consumers, are worried that AI will lead to lower quality news content, mis/disinformation and journalism job loss. To help ease these concerns, explain how humans — real, live journalists — are making sure that doesn’t happen. Also, emphasize the human elements of journalism that AI cannot provide.

How the research was conducted

We conducted three iterative studies over the course of this project in partnership with Benjamin Toff at the University of Minnesota.

- Our first experiment (Research Project 1) began by looking specifically at optimizing language in AI use disclosures. In consultation with newsrooms participating in the cohort, we began by generating different ways of describing how AI tools might be used in newsrooms, explaining what the tools allowed organizations to do, why they might opt to use them, and how humans were kept in the loop to ensure accuracy and ethical standards. We then tested how audiences responded to this language, first by asking a quasi-representative sample of Americans recruited on the research platform Prolific to rate these statements against each other, and next by conducting a large-scale A/B test with a separate sample recruited on Prolific (N = 3,995) where we could compare reactions to different disclosures against a control group who saw the same story but no information disclosing AI use. This experiment examined differences in reactions to one of four stories on differing topics when labels about AI use were varied by both AI use case and level of detail provided within the disclosure. For this experiment, we drafted the four stories with the help of generative AI and edited them for clarity. This was done to avoid using real news stories or real brands.

- Research Project 2 sought to gather data from newsrooms’ own audiences in response to actual AI disclosures placed on real news stories. Working with a cohort of newsrooms, we designed a shared survey instrument that each outlet published as a link in their disclosures, providing audiences with an opportunity to give feedback and voice their concerns and/or support. The specific AI use cases disclosed by these organizations and the stories in which these disclosures appeared varied widely, which makes interpreting aggregated responses to this survey more challenging. In addition, users self-selected into the survey, which could skew the sample toward people with strong feelings about AI. However, one advantage over Research Project 1 is that our survey involved each news organization’s actual users.

- Our second experiment (Research Project 3) was designed to build on what we learned from our previous two rounds of data collection. Here we again conducted an experiment similar to the first round of A/B testing, recruiting respondents on Prolific once more (N = 2,008), but we employed the same disclosure language across all conditions and made changes to the labels in response to the feedback we received from our audience survey. This included adding links to news organizations’ ethical guidelines as part of the disclosures themselves. Additionally, during this round of experimentation, we randomly varied the visual placement of labels to enable us to assess differences around when audiences might notice disclosure. We also used two actual news stories from cohort participants and named the organization when respondents were provided with the content, lending more realism to the experiment than our first experiment.

A more in-depth analysis of each project will be published later this summer. To receive the latest updates about this work, subscribe to Trust Tips, our weekly newsletter.

Have questions about this research or have research or related examples/case studies to share? Reach out to Trusting News Assistant Director Lynn Walsh at Lynn@TrustingNews.org.

Thank you!

Trusting News would like to thank the Patrick J. McGovern Foundation for making this work possible and for supporting the next phase of the work focused on AI education.

Also, Trusting News is grateful for the commitment from the 10 newsrooms in this research cohort. Without their willingness to experiment, the industry would not be able to learn these new insights and recommendations for how to move forward. Thank you to the following newsrooms and their journalists for their courage in experimenting at a time of great change.

- Bay City News Foundation

- Correio Sabiá

- Gannett

- inewsource

- KXAN

- Out South Florida

- Nucleo Jornalismo

- SWI swissinfo.ch

- Verified News Network (VNN) Oklahoma

- WBEZ, Chicago Public Media

At Trusting News, we learn how people decide what news to trust and turn that knowledge into actionable strategies for journalists. We train and empower journalists to take responsibility for demonstrating credibility and actively earning trust through transparency and engagement. Learn more about our work, vision and team. Subscribe to our Trust Tips newsletter. Follow us on Twitter, BlueSky and LinkedIn.