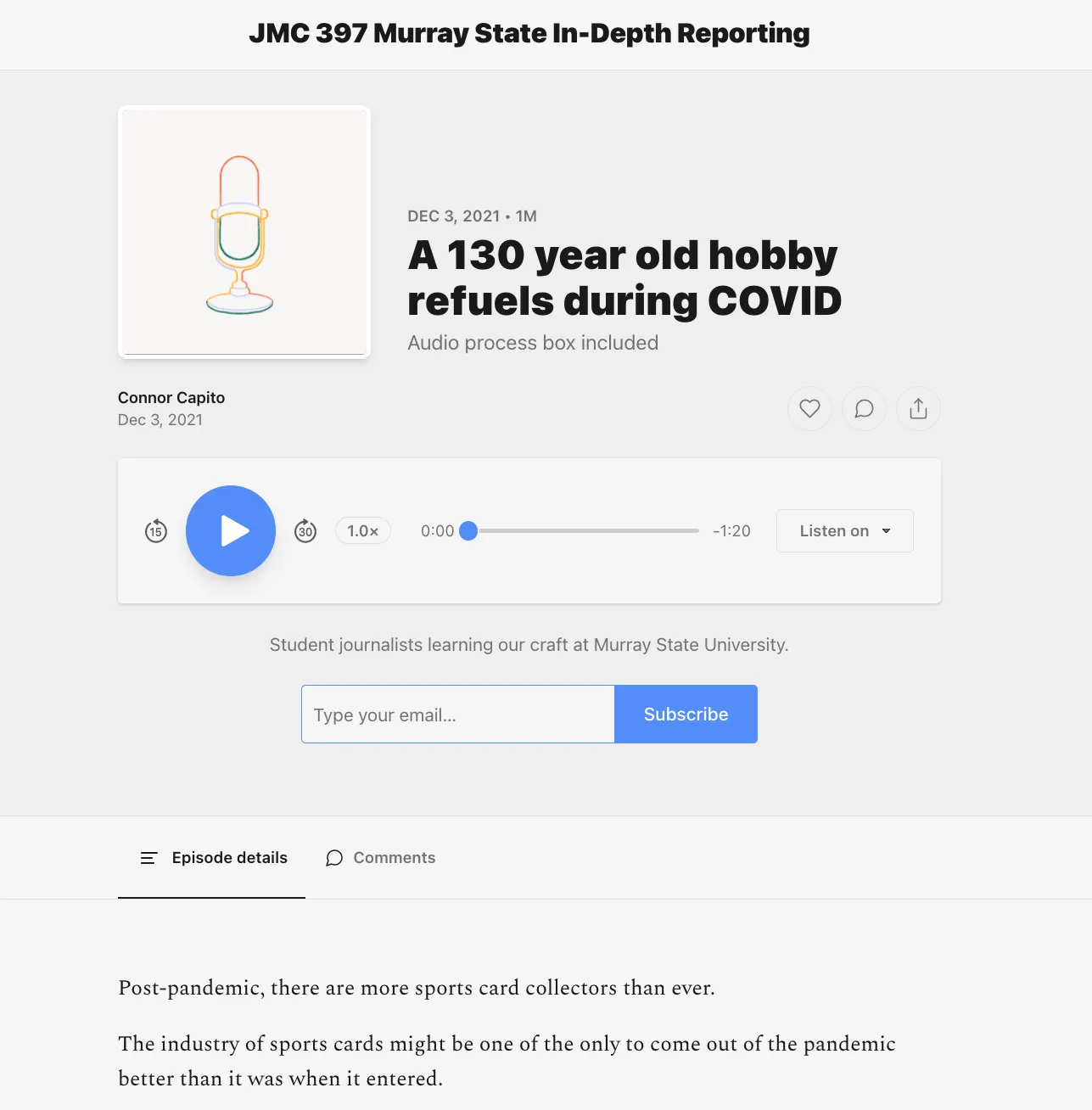

Leigh Wright, an associate professor of journalism at Murray State University, worked with students to explain their reporting process by recording short audio clips and embedding them at the top of their stories.

How journalism students are using audio boxes to explain their reporting process

At Trusting News, one of the key strategies we help newsrooms with is explaining their reporting process to their community. We do this because we know it can improve a user’s perception of the news organization.

Explaining the reporting process can take many forms, and we often experiment with newsrooms to see what formats work best for an explainer.

The format that works best can depend on the newsroom and the community they are serving. We have seen newsrooms experiment with explainers using boxes inside stories, in editor’s notes, in notes at the bottom of a story, in separate stories designed for print/web, in social posts or comments, and even in language added to on-air stories for TV and radio. (Our research shows adding transparency language on air can help build trust.) Check out this handout for tips on when to add an explainer to a story and learn more about the formats it could take.

Because we like seeing what formats work best for explaining reporting decisions, we were very excited to hear about what students at Murray State were trying: audio explainers.

A case study: Audio explainers at Murray State

Leigh Wright, an associate professor of journalism at Murray State University, worked with students to explain their reporting process by recording short audio clips and embedding them at the top of their stories.

Wright participated in a Trusting News class for educators in 2020. After the class, Wright created an assignment for students focused on transparency boxes — but with a slight change.

“I decided to try a new twist on the process box with my in-depth reporting class in the fall of 2021. During the summer 2020 training, I remembered someone mentioning that it would be interesting to see a process box as audio. Challenge accepted.… I chose an audio explainer file because it would make the students have to use their voice to explain their process, and a voice lends authenticity.”

— Leigh Wright, associate professor of journalism, Murray State University

For the assignment, the students produced a short audio file in which they told a story about how they reported on the story. Wright said this allowed students to “lift the curtain and let the audience listen to us describe how we chose to report a story and why.” (See the assignment Wright included in her curriculum here.)

One story focused on the increased interest in sports card collecting. In the audio explainer, the student reporter highlights:

- How he chose sources for the story. One of the sources was an expert on sports card collecting and was directly impacted by the increased interest in the hobby. Another source was working at a retailer experiencing the demand for sports cards.

- Why one source was anonymous. One source was unnamed due to the company policy of where they worked.

- Where he looked for information. He provided information about where he looked for reliable data on the hobby.

Another story focused on sorority and fraternity recruitment at Murray State. This audio explainer:

- Explains the student reporter’s connection to the story. The student talks about her experience during recruitment and why she wanted to look into this topic.

- Explains what the reporter learned from the story. The student explains what she learned during the reporting process, both about the story topic but also about the journalistic process.

- Adds context to the story. The student explains what recruitment is, adding important context to help someone understand the story better.

- Explains how the reporter got in touch with a source. The student explains how she went to the source’s office for the conversation and information for the story.

- Explains what she wishes she would have done differently. The student explains how she would have not said it was for a class assignment and instead said it was for a news story.

- Explains how she navigated an ethical issue of the source not knowing the story would publish. The student talks through an ethical dilemma of not telling the source the information and the initial conversation they had was for a news story. She explains she was able to use the information from the source by reading the quotes back to the source before publishing.

In both of these examples, the students were able to provide transparency around the reporting process, answering important questions about where the information came from, why they talked to the sources included in their story and why they chose to report on the story in the first place. The students also provided information about themselves and their connection to the story, humanizing themselves in the process.

(Educators, would you like to learn how to include trust-building strategies in your teaching? Start with these sample assignments.)

Wright said she is planning to have the students do this assignment again but might make some changes, including using a different platform when publishing the stories.

“Substack proved to be a bit difficult for students to navigate, but that may be because it was a new platform,” she said. “It occurs to me, too, that this exercise could be used as a podcast series in which the students explain their reporting process and talk with their peers in class about the challenges that they faced and how they produced their stories. The podcasts could be a good way to wrap up the semester and have them really dig in and reflect on their reporting process.”

A Q&A with Leigh Wright, the journalist behind the work

Read the Q&A with Wright below to learn more about how the assignment evolved and how students implemented the audio explainers in their reporting.

Trusting News would like to thank Leigh Wright and the Murray State In-Depth Reporting class for their time, effort and dedication to building trust with their community through transparency and engagement strategies like these. Through this work, we are able to learn more about what works best to build trust with the public. Without their willingness to experiment, we would not be able to share what works best for building trust with the journalism community. If you are experimenting with building trust, let us know here.

Where did you get the idea for having students turn explainer boxes into audio explainers?

I attended (virtually) the Trusting News training for educators in the summer of 2020. During those sessions, we looked at some sample assignments. One of those involved process boxes. I tried a process box in the fall of 2020 in my journalism capstone class as a way for students to explain their reporting process on the election. Our stories were housed on a website, and I found the process box to be a little clunky for the online platform. (See an example here and below.)

We posted a link to the explainer on social media too.

With the experiences from fall 2020’s capstone in mind, I decided to try a new twist on the process box with my in-depth reporting class in the fall of 2021. During the summer 2020 training, I remembered someone mentioning that it would be interesting to see a process box as audio. Challenge accepted. I tweaked the assignment from the sample assignment. I chose an audio explainer file because it would make the students have to use their voice to explain their process, and a voice lends authenticity.

Plus, I believe that all students need additional experience with recording and editing audio that can be embedded into online stories. Reporters need to be able to speak and write about their process as the general public does not know what all goes into producing news stories.

What issue related to trust were you trying to solve?

One of the slides that stood out to me during the virtual training showed a stat that only 21 percent of Americans had ever spoken with a reporter. I thought back to my own career and realized that we often went to the same people for interviews, and those people understood the reporting process because they were the ones we interviewed. We had built those relationships and that trust. But if only 21 percent of Americans have ever talked with a reporter, that means that 79 percent have not and don’t understand the reporting process. By showing and telling the reporting process, we can lift the curtain and let people see (and hear) behind the scenes so that they understand why we chose the angle to report, the sources we used and any other considerations that went into reporting the story. The more that we educate our audience about our process, the better that we can rebuild the trust.

How would you describe the effectiveness of the content and strategy?

I think it was effective. I queried my students with a reflection, and eight of the 11 said they thought explaining the process was needed. One student wrote, “Transparency is key.”

The ones who did not answer did not complete the reflection assignment even though they had completed the audio process box.

Describe what it was like to produce this content.

I asked several students to reply to this question. Here are their responses:

From Jillian Smith, who graduated in May 2022 with degrees in journalism and political science:

“For me, it was not difficult to write the story and bring this story to life. It was more challenging to actually sit down and think about why I talked to my sources, why I asked one source a certain set of questions, but not another source, etc. When writing articles, I focus on who the best person to interview for the story is. This activity made me really do a deep dive into the articles I have written and question my techniques. I have a greater appreciation and even understanding of my own writing because of this assignment.”

From Maggie Helms, who graduated in May 2022 with a degree in journalism:

For me personally, creating this content came more naturally than the actual story itself. An audio process story sets it to where the journalist is the primary source. When writing about your process, there is no one more authoritative — no one more credible than you. It is a unique opportunity to reflect and relax. This kind of contemplating encourages self-awareness. Not only does it build trust with your audience, but it gives you the freedom to claim your mistakes.

Would you use this trust-building strategy or content again?

Yes, I am planning to use this exercise again in my in-depth reporting class this fall. During fall 2021, I introduced it in November, which is near the end of the semester, so students were only able to use it with one story. I will introduce the concept earlier in the semester and require the audio explainer to be included with at least half of their stories produced during the class.

Typically, I have students write between five to eight stories per semester in this class. They have to cover at least one governmental meeting, and they have to write at least one story in which they have requested documents through our state open records act. They also have to produce enterprise stories from a specific beat on campus or in the community. Examples: Greek life, sports, crime, student life, etc.

How would you rate the difficulty of producing this content?

From Smith:

I would rate the difficulty of producing this content as a five. It was not that difficult once I was in the hang of thinking about why I spoke to certain people, why I asked them questions, etc. At first it was challenging because I never really thought about why I did these things. I just did them without thinking too much into it.

From Helms:

If I were to rate this in terms of wing sauce, it would be mild buffalo — a challenge but one that you choose.

How would you describe the journalists’ response after publishing this content?

Again, this was a class exercise so it’s a little different from a newsroom. For the most part, my students seemed to like this exercise. A few of them called it unconventional since they had never done it before and had not seen it. One student said the only place he’s ever seen the process box concept was in my classroom, and he considers himself an avid news reader and news consumer. He also likened the exercise to an Easter egg like what’s found in a movie. A little extra that leaves the audience with more. That same student also pointed out in the reflection that these process boxes take a bit of time, and that it might be difficult to do when a reporter is already busy with multiple daily stories.

Please add any other thoughts or comments you would like to share with the journalism industry. If you would recommend other newsrooms try this approach, what would you say to persuade them?

Absolutely, yes. If we want trust from the public, we, as journalism educators, must equip our students with the tools that they need to tell their story. By equipping students with trust-building strategies as they are entering the business, they can be the ones who drive changes in the industry. From my experience as a reporter for 16 years, we often simply go through the reporting process because we are juggling so many stories a day, or at least I did at my newspaper. Find a story, check. Figure out our interviews and documents, check. Write story, check. Repeat, check. So many times when I wrote stories, I went through the motions, and I took the writing/reporting process for granted. I realize that reporters in newsrooms today are even more stretched than we were when I reported, but we shouldn’t use that as an excuse. (Disclosure: I left the daily newsroom in 2009 to finish my graduate degree and transition into journalism education.) If we truly want to change the public’s perception of reporters, we have to be willing to tell our story as a way to rebuild trust. We have to talk about what we do, why we do it and how we do it. Rebuilding trust is critical in today’s world.

At Trusting News, we learn how people decide what news to trust and turn that knowledge into actionable strategies for journalists. We train and empower journalists to take responsibility for demonstrating credibility and actively earning trust through transparency and engagement. Subscribe to our Trust Tips newsletter. Follow us on Twitter and LinkedIn. Read more about our work at TrustingNews.org.

Assistant director Lynn Walsh (she/her) is an Emmy award-winning journalist who has worked in investigative journalism at the national level and locally in California, Ohio, Texas and Florida. She is the former Ethics Chair for the Society of Professional Journalists and a past national president for the organization. Based in San Diego, Lynn is also an adjunct professor and freelance journalist. She can be reached at lynn@TrustingNews.org and on Twitter @lwalsh.