After noticing an uptick of inappropriate comments, personal attacks and misinformation on COVID-19-related Facebook posts, a team at the Keene Sentinel — James Rinker, the digital community engagement journalist, and Cecily Weisburgh, an executive editor — made the decision that it was time to disable comments on posts related to the pandemic.

Why the Keene Sentinel disabled commenting on certain Facebook posts

It’s all too common for comment sections connected to news stories — on their own platforms and on social media — to be filled with bad actors.

Many journalists who have been tasked with moderating comments know it’s challenging to sift through oftentimes incredibly rude, accusatory comments while also trying to combat misinformation.

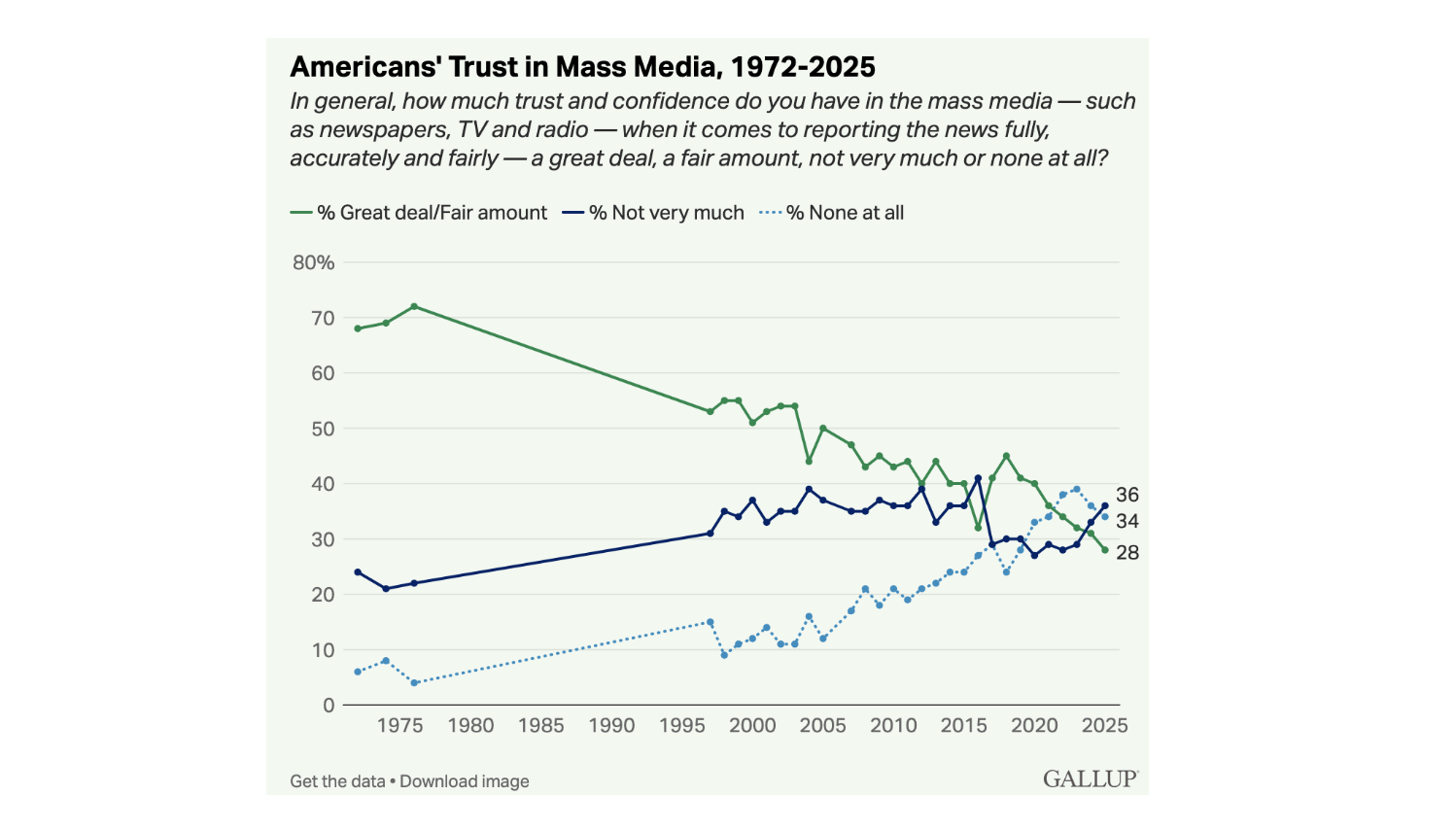

But beyond it being a taxing job, research tells us that perceptions of the credibility of journalism are also affected by what happens in comments. The Center for Media Engagement found that “uncivil comment sections can change impressions of the news and may hurt the news brand.” Another study found that when users are complaining about a story, the bandwagon effect leads other users to trust it less or think it’s less important.

That means if we let comment sections spiral, we’re actively harming the trust people have in our journalism. And if we as the journalists don’t take responsability to help steer the conversation, who else will? (We recently wrote more on why it’s important journalists moderate comments.)

So what if journalists did a better job of removing bad actors and validating good behavior, or made the call to fully remove comments that weren’t producing insightful conversation?

What if instead of letting negative comments fester, journalists used comment moderation as an opportunity to tell a story of their values of promoting productive conversation, and made it clear they stand for civility?

A case study: How the Keene Sentinel took a new approach with Facebook comments

After noticing an uptick of inappropriate comments, personal attacks and misinformation on COVID-19-related Facebook posts, a team at the Keene Sentinel — James Rinker, the digital community engagement journalist, and Cecily Weisburgh, an executive editor — made the decision that it was time to disable comments on posts related to the pandemic.

The newsroom already had an active commenting policy in place, and they would often moderate comments and ban commenters who continually crossed lines. But because of the nature and volume of the comments related to COVID-19, and because of a lack of staff capacity and time, they felt like keeping comments on these stories was no longer serving those conversations. Weisburgh noted that the comments actually seemed to be having the opposite effect, potentially harming people’s perception of the organization.

After getting buy-in and feedback from the newsroom and the publisher, they published a column outlining the new policy and shared it on Facebook.

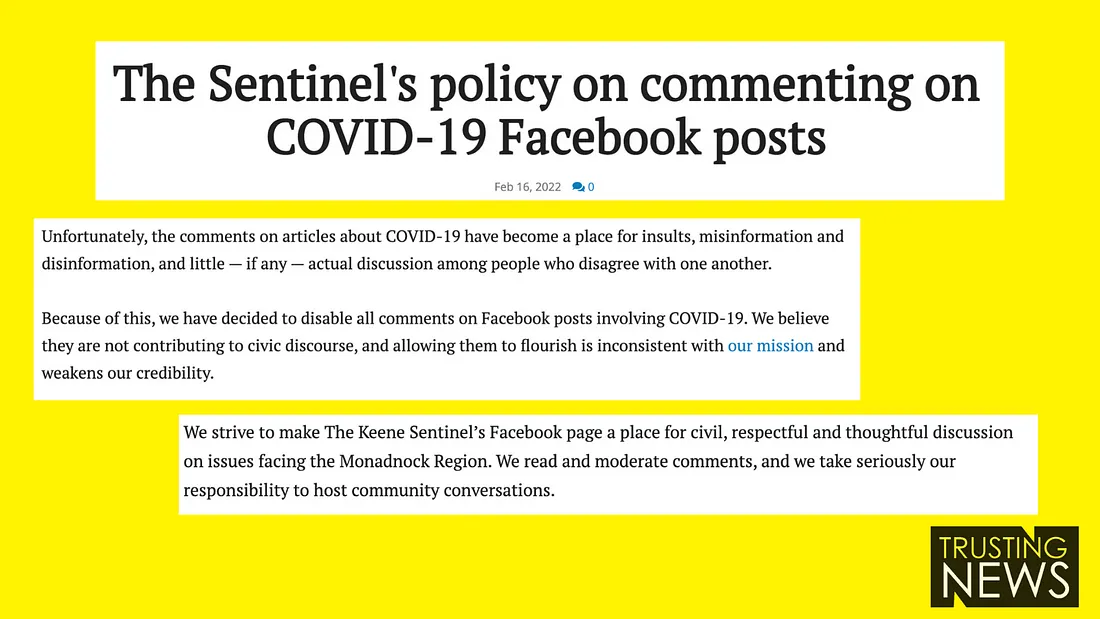

Here’s part of the policy:

We strive to make The Keene Sentinel’s Facebook page a place for civil, respectful and thoughtful discussion on issues facing the Monadnock Region. We read and moderate comments, and we take seriously our responsibility to host community conversations.

Unfortunately, the comments on articles about COVID-19 have become a place for insults, misinformation and disinformation, and little — if any — actual discussion among people who disagree with one another.

Because of this, we have decided to disable all comments on Facebook posts involving COVID-19. We believe they are not contributing to civic discourse, and allowing them to flourish is inconsistent with our mission and weakens our credibility.

You can read the full policy here, but here are some things I particularly love about it.

- They state their mission (to create a space for civil, respectful and thoughtful discussion) and tie the decision to turn off comments back to that mission. They also link to their commenting guidelines and make it clear constructive commenting will remain on other stories.

- They state that they value hearing from the public, and then back up that statement by offering alternative ways for people to reach out and share their ideas, opinions and insights.

- They let their readers know they want to help them navigate the news, pointing people to resources for spotting misinformation.

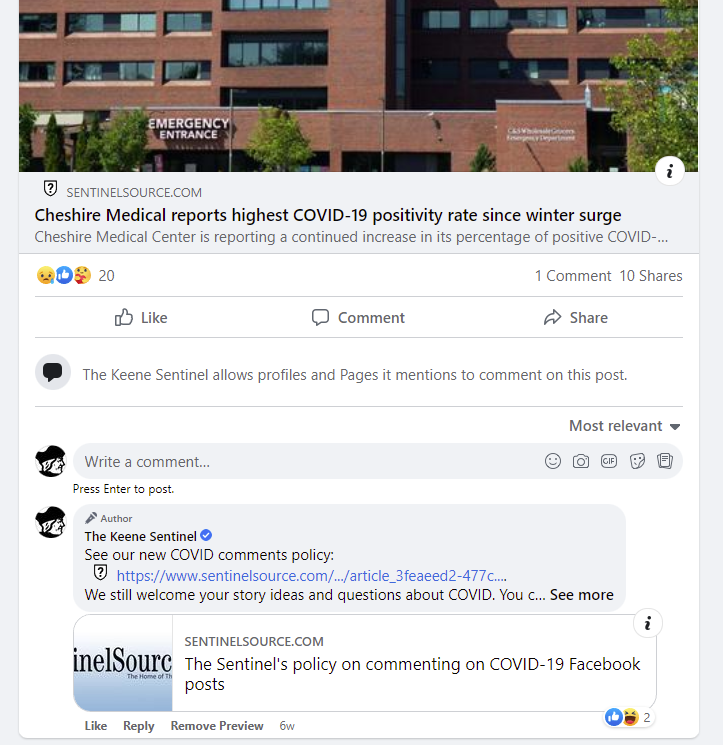

- They post a comment that includes the policy on every Facebook post where the comments are disabled, demonstrating proactive transparency with their readers.

Weisburgh said while they did receive some pushback and criticism of the new policy after publishing it, overall, their audience’s response was positive. The Sentinel hasn’t seen any decrease in their engagement or reach on Facebook, and actually had some supporters help defend their decision in the comment section on the post where they announced the new policy.

And anecdotally, with this new policy in place and with moderating comments on other posts, Weisburgh and Rinker said the overall number of unruly comments on Facebook seems to be down.

Read more about how the Keene Sentinel decided to remove comments, involved the newsroom in the process, and communicated their decision with the public, below.

Trusting News would like to thank James Rinker and Cecily Weisburgh, as well as the entire Keene Sentinel team for their time, effort and dedication to building trust with their community through transparency and engagement strategies like these. Through this work, we are able to learn more about what works best to build trust with the public. Without their willingness to experiment, we would not be able to share what works best for building trust with the journalism community. If you are experimenting with building trust, let us know here.

A Q&A with James Rinker and Cecily Weisburgh, the journalists who led the project

Note: The following responses have been edited for space and clarity.

Q: What issue related to trust were you trying to solve? What were you hoping users learned or understood better by consuming this content?

James Rinker: The biggest issue we hoped to resolve with closing off our comments for COVID-related articles shared was to combat the spread of misinformation and disinformation. Despite our best efforts over the course of the past two years of the pandemic, it grew out of control to continue manually moderating on our end. Through the statement we crafted, we hoped people would understand not only the reasoning behind this next step in our moderation efforts but could begin to reflect on their own role as digital citizens. There is simply too much misinformation present online for us to be the sole moderators of content that our readers post on our social media — it isn’t just on us anymore. Moderation of content online has now grown into a partnership, between us as an organization and those who engage with our digital platform. We each have a responsibility to think about the information that is shared and how it can contribute to an engaging online experience that benefits the conversations at hand.

Cecily Weisburgh: Comments on COVID-19-related Facebook posts became increasingly filled with vitriol and personal insults, as well as misinformation. There was no longer, in our view, any productive discussion or debate coming from them. We moderate the comments on our page, and felt we couldn’t keep up with them, nor could we see the value of allowing them to continue, and that was all to the detriment of our community and us as an organization.

We hoped that people would come away with a solid understanding of why we took this step, and that we still welcome and encourage their questions, story ideas and concerns, as well as the ways they can communicate with us.

Q: How would you describe the effectiveness of the content and strategy? Did you think it was effective? Ineffective?

James Rinker: Now that we have had this in place … it has proven to be effective in creating a more positive environment on our social media platforms and we receive feedback from readers who actually want to engage with us regarding our COVID-19 coverage in a constructive and respectful way. We wanted to make sure that our readers understood that we still value and welcome their input on all aspects of our coverage, and made that known by providing different methods of communicating that to us.

Cecily Weisburgh: I think it effectively communicated why we did this; it was clear that people received the message, the concerns came from when it clashed with their belief system, and how they believed our organization should have addressed the issue. Since the days of the initial post, we’ve received little pushback and believe our Facebook reader community has been much better served by it.

Q: Describe what it was like to produce this content. Did it come easily to you? Was it challenging? Did it make you think differently?

James Rinker: We already have a set policy in place for commenting on our social media platforms, so it was easy initially to begin the conversations about why this was necessary. I think the biggest challenge we had in this process was to consider the wording of the statement itself, and how it could be interpreted by our audiences. Our reasoning as to why we did this came quite easily — we just had to explain that clearly to our audiences and put ourselves in their shoes.

One thing that was important for me in producing this content was to provide resources that our audiences could use to learn more about misinformation online and how to identify it independently. More often than not, it could be a case in which someone doesn’t have the tools to recognize what is opinion versus fact online. By providing these resources, it helps us in continuing to be a trusted source of local news coverage and our readers in reflecting on their news diet and where they get their information from.

Cecily Weisburgh: I’d had this idea for a few months, but was going back and forth about putting it in place. I didn’t want to stifle conversation, and knew there would be backlash from people calling the policy “censorship.”

Moderating these comments by myself had also taken its toll on me, and I didn’t want that to be the driving reason for the change, either. After James Rinker joined the staff, he and I had some comprehensive and thoughtful conversations about this, and the pros and cons of a policy change. We agreed that the community would be better served by closing down the comments. Once we’d traveled the path to the decision, it was something we felt confident in standing behind. It made us think more deeply about what our “mission” was for our social media, and what and who was being amplified by allowing comments on these posts.

Q: Can you describe how long producing this content took? Did you involve other members of your newsroom? If so, can you describe what that process looked like and how long it took?

Cecily Weisburgh: It took a little over a month from start to finish. We started by approaching the local news editors, our owner/publisher, company president, and digital and design director to ask what their first impressions were. With the go-ahead from everyone, we started drafting the specific policy language, and the workflow (especially since Facebook doesn’t have a way for pages to disable comments). With a draft of the policy, we sent it around to the same people for feedback and received some good comments (including one that led to the discovery that we didn’t have our letters to the editor policy posted online!) We also sent it to Joy Mayer [the director of Trusting News] who really helped us with framing our explanation and strengthening the language.

James and I also drafted a response that we could send to people who might contact us with concerns about this policy.

Before we went live, I sent an email to the newsroom explaining why we were making the policy change. I wrote text and James created a short video tutorial on how to actually disable comments for the three newsroom staffers besides us who post on social media.

We also wrote a story for the print paper and online at the suggestion of our publisher, who thought that, even if these weren’t the same people using Facebook, they’d benefit from knowing our organization was taking a stand on this, and why.

Q: Would you use this trust-building strategy or content again? If so, would you do anything differently?

Cecily Weisburgh: We would. While we knew it would draw criticism from some people, we’re confident we gave readers a good understanding of how we came to the decision we did, and why, and a clear path of action forward.

Q: How would you rate the difficulty of producing this content?

Cecily Weisburgh: The hardest part was coming to the decision and the thinking behind that. Once we felt satisfied with our reasoning, articulating the policy and getting feedback was pretty energizing.

Q: How would you describe the user response to this content? If there are specific comments you would like to share, please share a link to the comment, screenshot, quote, etc.

James Rinker: The initial launch was how we expected it to be, in which we were accused of censorship and bias (here’s the Facebook post where they outlined the new policy.) However, we did have a great deal of support in our decision. So many of our readers also felt the fatigue that came with encountering the spread of misinformation and the harassment and personal attacks that were against others.

Cecily Weisburgh: The overall reactions were very positive toward our decision. The comments were more of a mixed bag. The critical comments focused on what people perceived as censorship, or that we violated their rights by restricting content. We also had a couple people say we should have done this much sooner, which is a fair point and an action, in hindsight, we wish we had been able to do. There were also positive comments from people who said they appreciated the new policy and defended our decision by replying to critical comments.

Q: How would you describe the response from your newsroom after publishing this content? Were people excited to work on this or see the content publish? Were people skeptical? Was it hard to convince people this was necessary?

Cecily Weisburgh: People in the newsroom, including the local news editors and reporters, were supportive, and we really haven’t heard any criticism. I think it helped to actually speak with each of the key people in the beginning (versus e-mailing) so we could have a back-and-forth discussion, and then the follow-ups for feedback on the specific policy went smoothly via e-mail. We were able to address potential concerns at the start by making sure each person’s questions were answered promptly before we wrote anything.

Q: If you would recommend other newsrooms try this approach, what would you say to persuade them?

James Rinker: Don’t hesitate to use the various resources and connections available to help in your newsroom’s work to make a change like this. From utilizing resources available to us from Trusting News along with taking a look at what other newsrooms did with similar policies and actions to ours, it helped us in the crafting of our own approach.

Cecily Weisburgh: I’d say that it’s worth the investment of time to make a change like this if it would benefit your community, and the results have borne that out. The key for us was planning and anticipating what the reaction might be, and having ways to address the concerns that came up. We also have not seen a hit to our follower count, interaction rate or social traffic thus far.

At Trusting News, we learn how people decide what news to trust and turn that knowledge into actionable strategies for journalists. We train and empower journalists to take responsibility for demonstrating credibility and actively earning trust through transparency and engagement. Subscribe to our Trust Tips newsletter. Follow us on Twitter and LinkedIn. Read more about our work at TrustingNews.org.

Project manager Mollie Muchna (she/her) has spent the last 10 years working in audience and engagement journalism in local newsrooms across the Southwest. She lives in Tucson, Arizona, where she is also an adjunct professor at the University of Arizona’s School of Journalism. She can be reached at mollie@trustingnews.org and on Twitter @molliemuchna.