News consumers often say they want stories that “just give me the facts” and “include both sides.” When asked what they’re looking for in responsible journalism, at the very top of the list for news consumers will be one word: balance. (At least, it’s at the top of the list from 81 user interviews conducted by Trusting […]

What does “fairness” in news stories actually look like?

News consumers often say they want stories that “just give me the facts” and “include both sides.”

When asked what they’re looking for in responsible journalism, at the very top of the list for news consumers will be one word: balance. (At least, it’s at the top of the list from 81 user interviews conducted by Trusting News partners.)

Often mentioned alongside the word balance are the words “both sides.” These are tricky concepts, of course. There are usually more than two sides.

So, what does that look like day to day, in coverage of social issues, politics and life in general? What makes a story feel fair, neutral or balanced? What makes it feel slanted or opinionated? And how do those elements play out in the decisions journalists make day to day about things like sourcing, word choice and headline writing?

Let’s talk about it.

As we continue to kick off our new initiative, A Road to Pluralism, along with our Pluralism Network, we’re going to dig into a series of challenging questions that we think are crucial for local journalists to address. We’ll talk about five topics that we believe are contributing to the perception that local news is part of the problem in a polarized society, rather than a trusted resource across the political spectrum.

(In this video, hear us talk about the five themes and what we learned in recent research with the Center for Media Engagement.)

We’ve discussed the value and challenges of local and national news and generalizations and polarization in news coverage.

Along with balance, fairness is another key concept often mentioned by news consumers.

Most journalists would say that they aim for and often achieve balance and fairness. Yet news consumers do not always recognize those ideals in the products we deliver and, very often, they do not give us credit for striving for them. In fact, they often assume the opposite — that we are actively suppressing some perspectives and highlighting others based on our personal and organizational beliefs and priorities.

Research shows that the words journalists use can alter the public’s perception of coverage, so it’s vital that journalists be clear and thoughtful in the language they use in stories. It’s also important to be aware of how our own assumptions or biases might influence those word choices.

What we’ve heard from local journalists

Here’s a collection of observations from our newsroom partners and other journalists who’ve gotten in touch with us on the topic of perceptions of stories’ fairness.

- Readers tell us they notice how we describe groups of people. One example they gave: If we’re talking about a certain class of lower-income voters, their perception is that if they’re republicans we describe them as less educated, and if they’re democrats we describe them as blue-collar.

- Too often our stories are well-balanced, but the headline is more sensational or seems to reveal a bias. Our copy desk needs to be in on these conversations about what causes mistrust.

- Teamsters were on strike, and a reader told us he was not happy with the story because it was only from the viewpoint of the teamsters. It didn’t have one sentence or statement from the company. The reader hadn’t thought before about how that might be all we had access to as journalists. He assumed that we cut all the management stuff or didn’t bother reaching out. He assumed the reporter agreed with the teamsters and assumed we had an agenda.

- A reporter wrote something like, “the governor, who is seeking re-election next year, …” in a story. It got us talking about how the decision to include that implies that we think there is a political motivation behind his work. This wasn’t a story about his political plans. Including that can feel to readers like putting a spin on his actions.

- A lack of context can imply that we think we’re telling the entire story. For example, if we fail to put a public safety incident in context, it gives the impression that a community is less safe than it really is.

- Focusing headlines on an individual lawmaker or person instead of what happened can lead people to think you are against that person. For example: when fact-checking something from social media, if it turns out what was shared or said wasn’t true, focusing the headline on the person who shared the false information can make some see the story as being negative about the individual. Instead, the focus could be on the false information.

- Frustrating was the typical complaint that our opinion pages are too liberal.

- There’s a segment of the population that will never be happy with the opinion page because it doesn’t represent them and only them.

- People see us as vultures. In reality, we have a lot of conversations about what makes something a story and whether we can do it ethically and responsibly.

- Putting things in quotes. One guy said in my coverage of something, someone referred to cancel culture, and I put that in quotes. He took that as an insult. Like it was dismissive.

- A listener pointed out what felt like inconsistencies to him around when we list a public official’s political party in a story. Or when we list the names of judges. I’m not sure we ARE consistent. The same can be true for when we run a suspect’s mugshot or follow an arrest as it makes its way through the criminal justice system. (More on inconsistencies in crime coverage is here.)

- One woman was really upset because we had photographed prom, and the photo on the front page was of two girls who had gone to prom together. She thought we were trying to embarrass them, or that we were implying they were a couple. Whether they were a couple or not, the reader had assumptions about our motivations for selecting that photo

- A reader said our only reporting about the vaccines was about how good vaccines are and where to get them. They said they wanted to see stories about people who won’t get vaccines. Our reporter told the reader no one would talk to her. We asked her to go on the record, and she agreed to. Are we working hard enough to tell that story?

- You don’t cover the other side. You only covered the vote yes committee. That made us realize there wasn’t a vote no committee. Are we too reliant on structures like that?

Questions we’re ready to see local newsrooms ask

With our new Pluralism Network, we’re committed to working with newsrooms to find solutions to these complex problems. On the topic of perceptions of stories’ fairness, here are some questions we’re ready to ask.

How do the way we write stories impact how fair they are perceived?

- What adjectives are used to describe people, situations, groups, etc?

- Are we consistent with the adjectives we use and when we use them? What about labels? Do we always use “republican” and “democrat” when mentioning a lawmaker?

- How are we writing headlines? What words are we putting in the headline to highlight what the story is about? How about social text? Is the same effort to be fair or neutral being made there?

What context is important if we want a story to be perceived as fair?

- How do we pick the focus of the story?

- What perspectives are we adding to the story?

- Which perspectives are we not including?

- When we add details about a person or situation, do we pause to consider how we’re deciding those details are relevant? And would that relevance be clear to the audience?

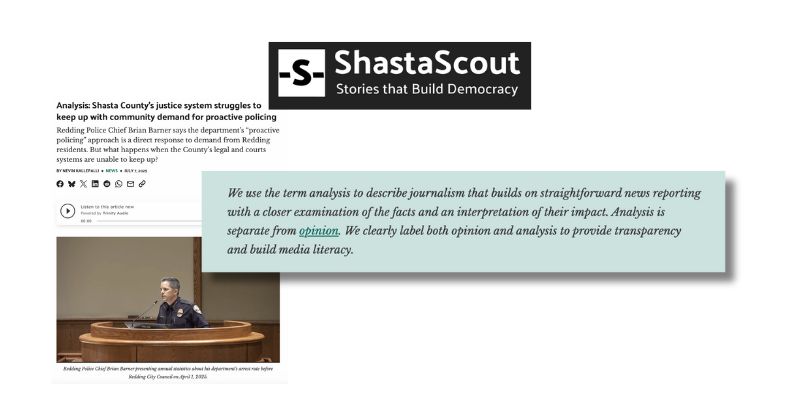

Users want us to focus on fact, not interpretation. What does that look like?

- When we insert opinion are we labeling it as “opinion”?

- If we offer any kind of “analysis” how are we labeling that?

- Do the labels appear clearly and follow when shared off the original platform?

- Do we explain what the labels we use mean, especially when it comes to opinion content?

Are we correcting our mistakes?

- We don’t like to make mistakes and try hard not to, but sometimes they happen, so how are we correcting them?

- Do we make our corrections policies public?

- When we make a correction, do we make the correction with humility? Are we willing to answer additional questions about the correction from the community?

- What if something isn’t wrong, but could be better? How are we addressing those situations?

- Is it clear that we place a high value on accuracy? Are we on the record that we want to know if we’ve gotten something wrong

How do sources impact how likely stories are to be considered fair?

- Who are we not including in our stories?

- Who are we including in our stories?

- How much do we include from each source? How many SOTs? How many quotes?

- Who did we speak to but not include in the story? Are we sharing that information with the audience?

At Trusting News, we learn how people decide what news to trust and turn that knowledge into actionable strategies for journalists. We train and empower journalists to take responsibility for demonstrating credibility and actively earning trust through transparency and engagement. Learn more about our work, vision and team. Subscribe to our Trust Tips newsletter. Follow us on Twitter and LinkedIn.

Assistant director Lynn Walsh (she/her) is an Emmy award-winning journalist who has worked in investigative journalism at the national level and locally in California, Ohio, Texas and Florida. She is the former Ethics Chair for the Society of Professional Journalists and a past national president for the organization. Based in San Diego, Lynn is also an adjunct professor and freelance journalist. She can be reached at lynn@TrustingNews.org and on Twitter @lwalsh.