COVERING ELECTIONS

When covering elections, a lot happens behind the scenes in newsrooms before the cameras start rolling and articles are published. Planning sessions often take place months in advance to determine the coverage strategy.

That shouldn’t just be about what issues and races to focus on. It should also be about being fair and ethical in your reporting. In today’s climate, credibility matters more than ever. People want news they can trust, especially when it comes to elections.

But trust isn’t a given. Most people are quick to assume bias or hidden motives behind the stories you’re telling, especially with elections. And with election coverage, you’re not just reporting news; you’re providing information for the foundation of a functioning democracy.

On top of this, we face other challenges: What happens when people can’t agree on what’s true anymore? Or when they’re living in completely different news bubbles? What’s the point of your reporting if the very audience you’re trying to inform doesn’t trust your integrity or accuracy?

It’s not easy, but in this pivotal moment, it’s crucial to double down on credible, rock-solid reporting. It’s not just about the stories you’re telling; it’s about ensuring your communities have access to information they can rely on, understand and use to make informed decisions, no matter where they stand politically.

When covering elections, it’s crucial to double down on credible reporting. It’s not just about the stories you’re telling; it’s also about ensuring your communities have access to info they can rely on, understand, and use.

Goals

This Trust Kit helps you:

- Communicate your election coverage strategy, and the planning and ethics behind it.

- Bolster trust and credibility amidst skepticism.

- Craft election coverage that resonates as fair, even-handed and reliable.

- Ramp up the impact of your election reporting.

- Respond to common questions, accusations and misinformation that surface during elections.

Basics for building trust with election coverage

Here are some foundational strategies to employ when covering elections.

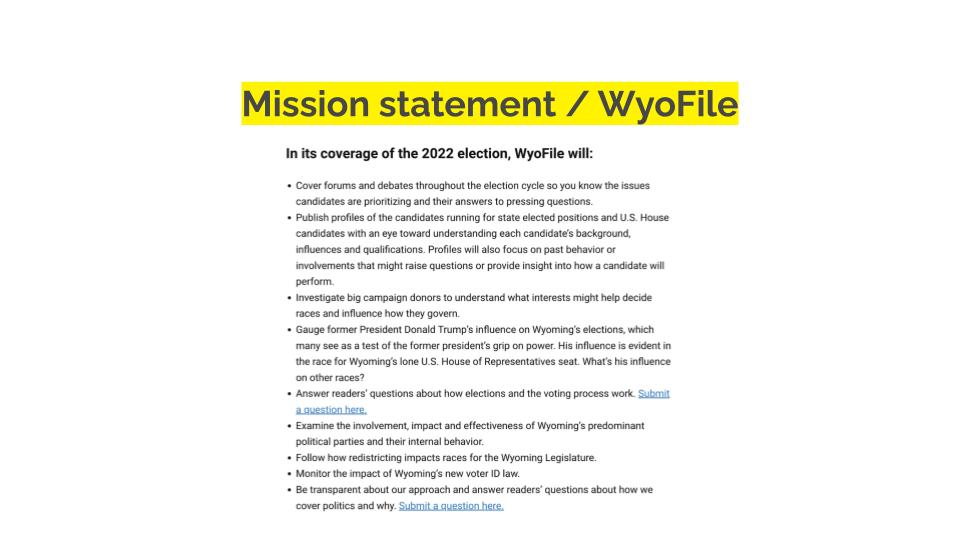

Explain your mission and goals

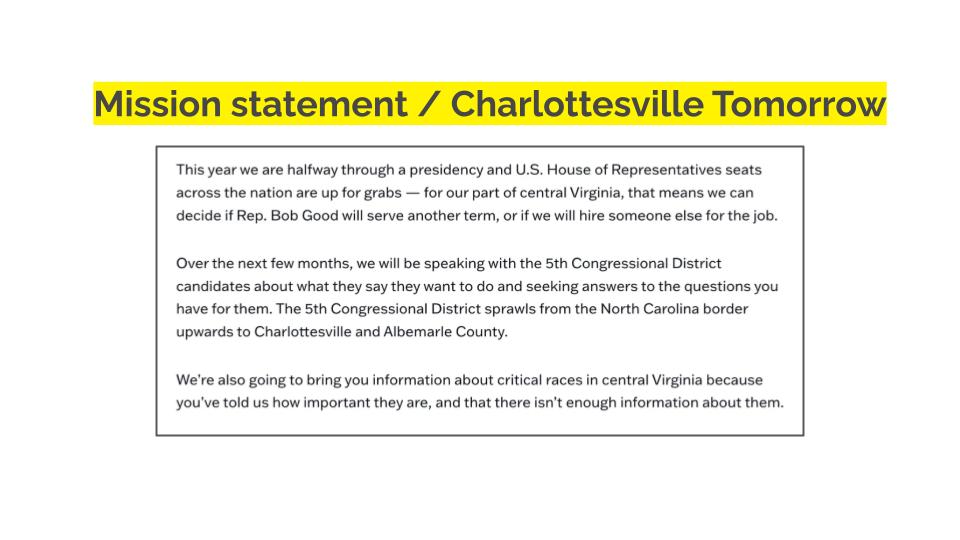

Many newsrooms meticulously plan their election coverage, deciding on topics, races and the overall approach in advance. However, these strategies often remain invisible to the audience, leaving reporters fielding accusations of bias and unfairness. We suggest a shift: Instead of keeping these decisions behind closed doors, share them openly. Explain story focuses, discuss prioritized issues and races, and articulate your coverage goals to foster transparency and understanding with your audience.

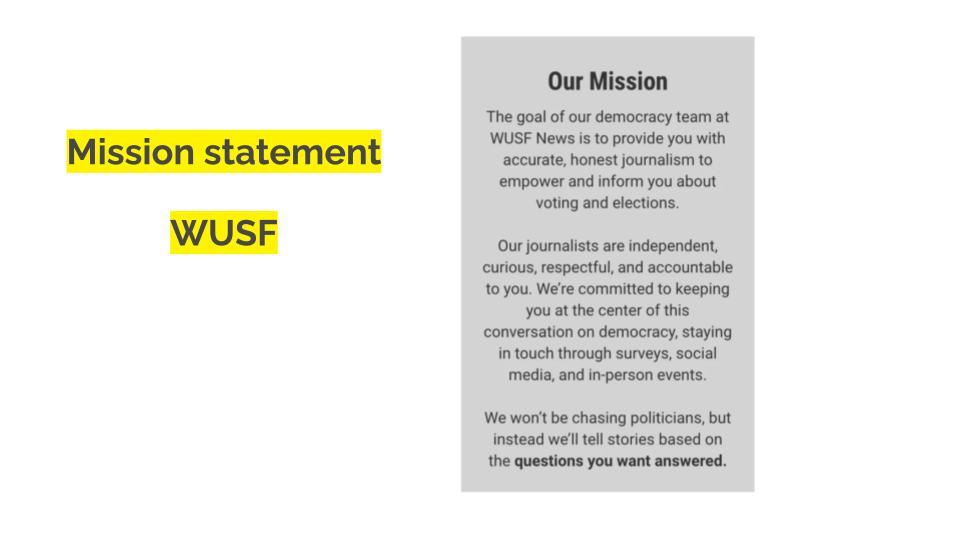

You probably have a mission statement for your newsroom. (If not, we have tips on creating one and making it public.) Organizational mission statements share the values of a news organization. They should go beyond “holding the powerful accountable” or “finding the truth” and should include specifics about how you select which stories to cover and what you invest your resources in.

A mission statement for your election coverage is similar, but instead of addressing your entire coverage, it focuses only on your election or political coverage. It should address how you cover races, politicians, voting and democracy.

A few key elements a mission statement for your election coverage should include:

- Your why: You want it to include why you do what you do. This could address questions like: Why is covering elections important to you? Who do you serve? What are your goals? Why are you covering (or not covering) specific races? Why are you focusing on certain issues? Why are you paying close attention to voter registration?

- Your who: Who are the reporters covering the election? What is their experience that lends credibility to the reporting? How can people get in touch with them?

- Your how: How do you conduct your work and accomplish the goals you laid out? How will you cover the races and politicians? What kind of information will you be reviewing and gathering? What sources do you trust? How will you ask candidates questions? If people do not respond to you, how will you handle that?

- The what: This is the actual thing you do. Where can people find your election coverage? How can they stay up to date on the latest news about the election? Where will you be posting updates? How often will you be updating your reporting?

If you want to go even further and add more transparency you could:

- Discuss conflicts of interest and how your staff avoids them or handles them.

- Address complaints of bias and having an agenda directly by discussing how you work to be fair and what it means to be independent.

- Provide an easy way for community members to contact you and/or ask questions about the election.

Remember that with all of this, you want to tie it back to the community. While you can highlight all of the work you do, you don’t want it to sound self-serving. The goal isn’t to make yourself look impressive. At the end of the day, the reason you do all of this information gathering and fact-checking is for the public. Be sure to tie back all of the work to that point.

Mission statements for your election coverage are also a great tool to:

- Hold your newsroom accountable (internally and externally) because you are on the record about what you aim to achieve

- Shine a light on your values, ethics and goals

- Help the newsroom respond to comments from the community (because you’ve already articulated what you want people to know)

- Keep your coverage consistent and tied to goals

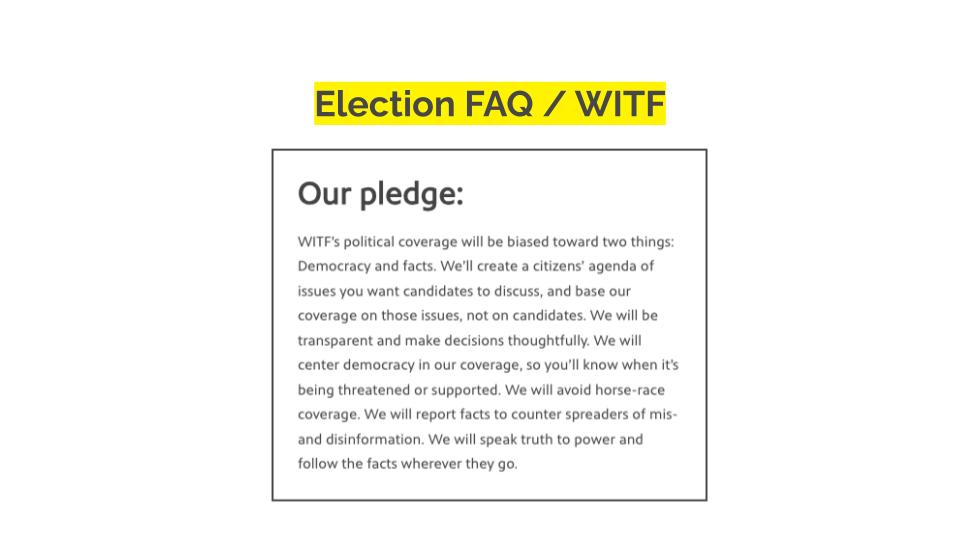

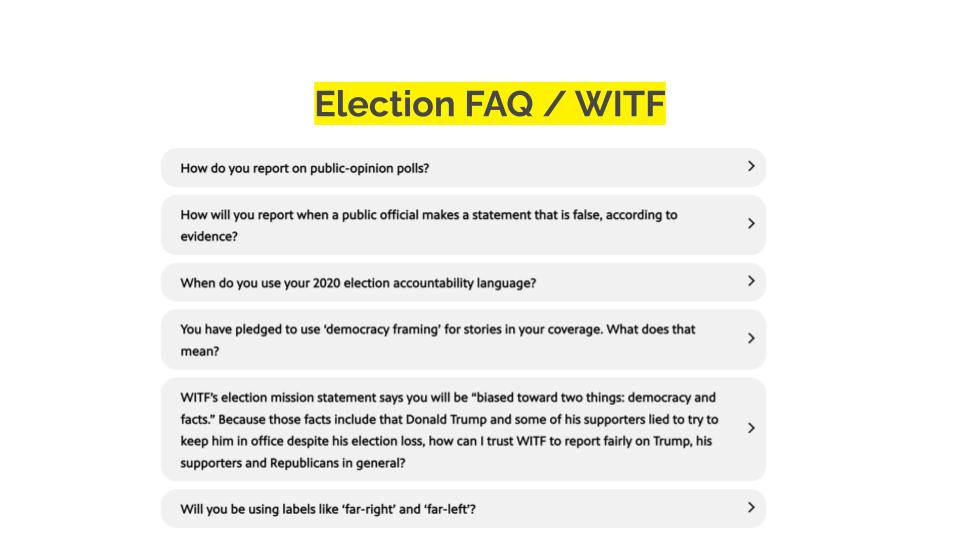

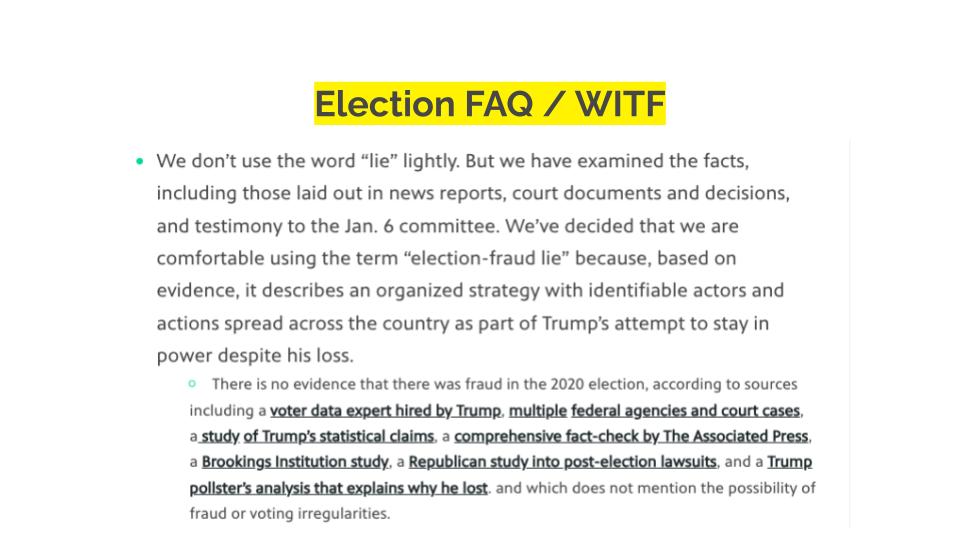

You can also create an FAQ page. Unlike an official About Us page or policy page, an FAQ can feel less formal — almost like a conversation between a reader and a journalist. It’s also easy to add to or edit and it often doesn’t need the layers of editor approval official policies need. Another feature that can make an FAQ page especially useful is the option to make an on-page link — often called an anchor tag — for each headline. (This is a common option in content management systems, so ask around if you’re not sure how to add one in yours.)

Learn more about creating an election FAQ page in this post.

Avoid polarizing words and frameworks

Too often, journalism amplifies extreme views and ignores more nuanced ones. It reinforces the idea that people are split into political camps. It oversimplifies or stereotypes groups of people and gives the impression that people who agree on one thing likely all agree on completely separate issues.

Our team and our partner journalists have asked news consumers to describe the signals that make stories feel fair or unfair. People often point to simple word choices — small things that seem to convey where the journalists are coming from and how they feel about the sources and ideas presented in their stories.

Was a win “surprising”? Is someone’s stance “strident” or “relentless” or “unapologetic”? Does a family’s monthly grocery bill add up to “only” $1,000? (And what does putting words in quotes signify about the writer’s attitude toward the words?)

Journalists’ word choices and framing of stories communicate a mix of literal and connotative meanings.

Working alongside partner newsrooms, we learned that by being more aware of word choices and story framing, journalists can avoid sending accidental signals about their own views and about whose values the content is reflecting.

Advancing Democracy newsrooms used the checklist while covering the election and politics in late 2023. The journalists were asked to take notes on which stories they used the checklist for and answer questions about any changes they made related to sourcing, language (in the story and headline) and story framing.

They told us the checklist helped them:

- Take a closer look at word choice, especially in headlines. Sometimes the language changes were as simple as adding qualifiers like the word “most” instead of attaching descriptions to whole groups of people or beliefs. Other times the changes made in language were more nuanced.

- Deepen the number or types of sources included in the story. In reporting on stories related to the conflict between Hamas and Israel, one newsroom included information about why they quoted the sources they did, including the sources’ credibility and expertise. Some of the explanations included: serving in the Israeli military, working in a Palestinian town surrounded by Israeli settlements, having a family member abducted by Hamas and having family that survived the Holocaust.

- Add more context to stories. In a story about the Michigan House not moving a resolution forward, the reporter decided to explain why the legislation did not move forward instead of just saying it didn’t get approved. The reporter said their timing with the story was different than other news outlets.

- Focus on commonalities instead of differences. For a story about two council members, who have different views and are on opposite sides of the aisle, a reporter decided to focus the headline and framing of the story on what the council members have in common, instead of focusing on their partisan differences. The headline highlights their military service and the common belief that more should be done for veterans than “a free appetizer on Veterans Day.” The reporter said, “I really liked this story! I felt like it was a good opportunity to celebrate collaboration.”

Want to work on eliminating polarizing language and story framing in your reporting? Here are some resources to help:

- The anti-polarization checklist to help you pause and examine how your story might be perceived by people with different values and experiences.

- A list of words to watch out for, including language that might spice up a story but can also convey a perspective or attitude, or words that might give away your own assumptions or viewpoints of an issue.

- A checklist to run your headlines through, because users make snap judgments about your coverage, so careless headlines can quickly turn off and undermine the careful work you put into stories.

Explain polling

Political polls are a lot to navigate. There are new ones continually. They seem to contradict each other. The validity and structure vary a lot. It’s hard to know which ones to trust, or if we should even bother paying attention.

As journalists, we learn how much credence to give polls. We learn to look for independence in the pollsters. We inspect their methodology. But are you explaining any of that to your audience? And if you run your own polls, are you explaining to your audience how you do it — and why?

The 19th did this with a public opinion poll they recently conducted in partnership with SurveyMonkey. When they published the polling data, they included explainers that went in-depth about their methodologies, how they were using the data, and why they felt it was important and relevant to their audiences.

The top of their landing page starts with the mission of the poll (that they wanted to find out what women, particularly women of color, and LGBTQ+ people, think about politics, politicians and policy). It also includes how their goal was to highlight and focus on the experiences of the communities the organization serves — not to do polling around specific candidates or races.

They also published an FAQ-style article on how the poll was conducted, where they use clear, straightforward language to explain:

- Why they did the poll

- How the poll worked (and general information on how polls work)

- How to know if the answers are accurate

- The limitations of the survey language

And, at the end of this page, they acknowledge the limitations of polling data, but explain why it is that they still trust the data:

We especially love how in the subsequent stories where they use this polling data, the newsroom continually points back to these explainers. (Remember, most people won’t see a project landing page, so think about how you can insert those explainers in all the other places where people might find that data and have questions.)

Here are a few other examples of newsrooms explaining polling:

- Video: A look at how the PBS News/NPR/Marist Poll is conducted

- The Atlanta Journal-Constitution explains how they conducted their own poll

- A Washington Post story explains a presidential poll

Address misinformation

At Trusting News, we’re often asked how journalists should handle misinformation. This is not surprising, given how both the public and journalists agree it’s a major issue. But research shows that as much as journalists think it’s a problem, they rarely address it in their reporting. (In this Pew study, two-thirds said almost none of the stories they worked on in the past year had to do with false or made-up information.)

If we want people to be able to decipher good information from bad, to turn to us as a credible news source and to trust that we work to combat misinformation, we have to start addressing it publicly. Here are some ways journalists can do that.

Empathize with people and validate skepticism

We can often categorize people who share and believe misinformation as far beyond the realms of reality and totally unreachable. “Those people” must not care about facts, right? Or worse, they might be trying to manipulate those around them.

Remember, though, that many people are well-intentioned when it comes to the accuracy of information, but they just lack the skepticism and tools to be able to discern what’s credible. Also, it’s good to remember that everyone (even journalists) is susceptible to misinformation.

With this in mind, can we try to extend more empathy to our audiences when they share information that’s not legit? Can we encourage them to be skeptical and make thoughtful, careful choices? To validate that it’s smart for people to be wary of what they see online and that they should absolutely question the values and options that drive information? And can we point them to resources and tools that might help them do this?

Don’t ignore rumors

When misinformation arises in our communities, especially in conversation spaces your newsroom owns or helps moderate, it often does more harm to not acknowledge it. Instead, address it and set the record straight.

We’ve shared this example from reporter Vic Micolucci of WJXT in Jacksonville before, and we continue to really appreciate how he directly addressed when rumors were swirling online that journalists had altered photos of Florida beaches reopening during the coronavirus pandemic.

It’s perhaps most important to address misinformation and rumors when they are active and spreading. But we also encourage you to talk to your audience about your newsroom’s approach to handling misinformation more generally. Talk about how you don’t tolerate or spread misinformation. Be honest that it’s an issue for you too, and how it impacts your credibility and your reporting. And then if you can, back up those claims with specific examples from your reporting.

Publicly correct your mistakes

We know some journalists are concerned about making their corrections too visible. Won’t that make people question your reporting even more if they know you make mistakes? But research from Pew shows the opposite — seeing corrections to news stories actually increases people’s confidence in the work.

If the public already thinks journalists don’t care about getting it right and are worried journalists are publishing unverified mistakes, then it’s important we start addressing our mistakes publicly. That lack of faith in our commitment to accuracy is often cited as a reason for low trust.

Our own research with the Center for Media Engagement showed that people who lean right pointed to prominently correcting errors as a key factor in trust. Do it consistently, and consider explaining how an error occurred and why the correction was necessary. Our Corrections Trust Kit can help you audit your own practices.

Monitor and respond to comments

The comment section isn’t always a fun place to hang out. There are usually some nasty comments, trolls and other things we’d probably like to just ignore.

But we know that negative comments impact people’s perceptions of a news organization and its credibility — and that too often, we’re not present to defend ourselves. If people are questioning the fairness and ethics of your elections coverage in the comments — or making any accusations or assumptions about your motives or reporting processes — it’s worth taking the time to respond and clear up misconceptions.

When you see someone making a negative assumption or accusation about your work, try to turn their complaint into a question. What kind of information are they needing, or missing, that’s causing them to assume the worst? Try answering and redirecting them in a neutral tone.

Get curious about people’s perceptions of your election coverage (even negative ones). Watch for questions people have about the election process that you could help answer, and invest some time in engaging with and responding to your community.

Also, it’s good to keep in mind that many more people read the comments than actually comment themselves. So that means it’s worth it to defend yourself and your coverage, even if the original commenter seems unreasonable. A lot more people are seeing those comments (and your responses) than are weighing in on the conversation.

Not sure how to jump into comments? We have tips and suggested language for how you can defend your work without sounding defensive. We also have a Trust Kit on engaging through comments that can help.

Make endorsements (and opinion content) clear

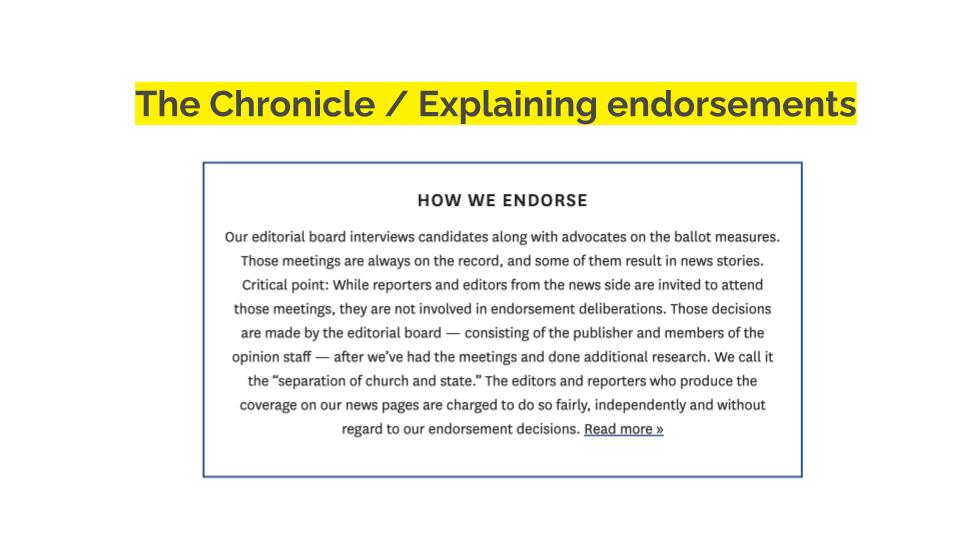

If your news organization has an editorial board that writes endorsements, runs nationally syndicated opinion content about the election, or includes local or guest opinions, be extremely careful to label and separate this content from your news coverage.

So often, we see people get confused by endorsements or opinion pieces, thinking that opinion content stands for the entire paper and staff. And this makes sense, right? Typically endorsement headlines have the newsroom’s name, colon, and then an opinion on who to vote for. Without explanation, of course people get tripped up by this and think it’s a signal of bias in the actual news cover.

Start by making sure you label all opinion content with clear wording (using the word “opinion” works best!). Post the link like you’re going to share it on social, and see if the opinion label transfers to all platforms you publish that content on. Even if your news organization doesn’t share opinion content on social, others could, and you want to make sure labels travel with the story on every platform.

We also recommend that in addition to clearly labeling all opinion content, you explain whose opinion is being shared and why. Whether guest op-eds or endorsements, give a brief explanation of why your news organization is highlighting different opinions and viewpoints in the community. State how those opinions are independent and do not influence news coverage. Point to how you’re trying to be fair and present opinions from all valid sides of an issue.

Articulate this in a few sentences and put it at the top of every editorial or opinion piece as an editor’s note or in a box — anywhere people might see it. Here are some examples of how the San Fransisco Chronicle and The Tennessean did this.

Reach beyond news junkies

More and more people are tuning out the news, noting that it feels overwhelming and irrelevant to their lives. This is harmful, of course, to journalists’ overall relevance and newsrooms’ sustainability. But it also has deeper, and more dangerous, social implications.

If we as journalists want to fulfill our role as a public service, we should be actively helping our audience better navigate the news — especially when it comes to elections. After all, we serve the public we have, not the public we wish we had.

Here are some strategies for how you can do that.

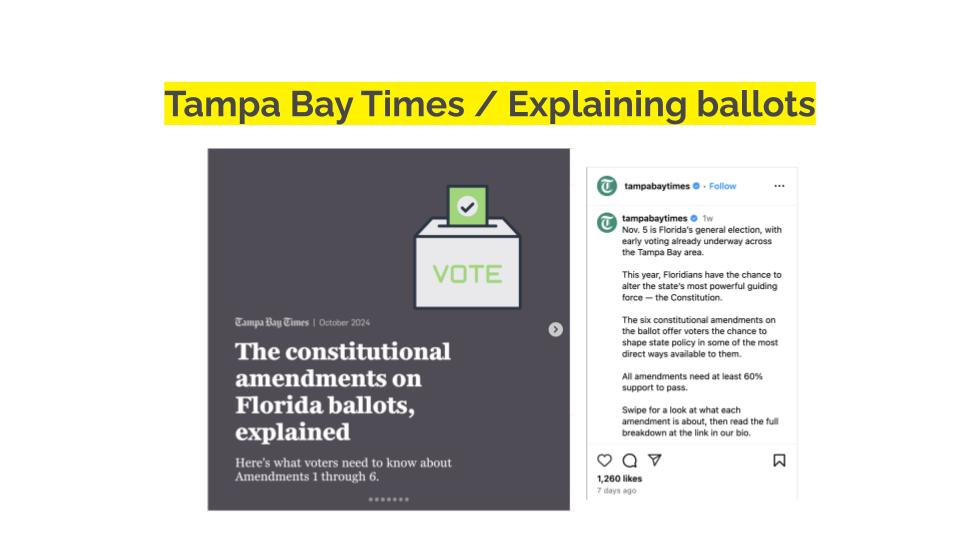

Make basic information easy to find

As journalists, we strive to provide in-depth, thoughtful analysis and coverage of issues and candidates for our communities. But sometimes we can miss the fact that many people are simply seeking the most basic of election information.

Basic information means: Which candidates are running? What initiatives will people be voting on (and what language will be used to describe these on the ballot)? Where can people register to vote? Or turn in their mail-in ballots?

While you’ve likely already answered these questions in your coverage, remember most people just see a small portion of the coverage you provide. And they might not have seen these basic facts if they were inside longer stories.

On top of that, many people in the public are just now starting to pay attention to the election, or will only seek out information when they’re filling out their ballots, or getting ready to go to the polls.

Start by imagining that everyone is a first-time voter. What would people need to know about the election? How easy would it be to understand your coverage? Would people be able to search and find answers to things on your website?

Make a list of those questions, and then think about the best way to provide those explanations. Some ideas: You could gather this or add it to an FAQ page that links to the coverage you’ve done or a box that runs alongside election coverage, that links to this basic information. We love this example from the Times Union. They created an FAQ page that explains: what they cover, how everyone named in a story has the chance to comment, independence between editorials and news, and reporters’ own biases.

Help people navigate the news

Most people have a casual relationship with the news. Things that we take for granted — that information changes quickly in a breaking news situation, for example, or that responsible journalists confirm information before publishing — are just not universally understood. Our News Literacy Trust Kit offers a range of ways to inject information about how news works into our coverage.

You don’t have to write these explainers all yourself. Link to what other organizations have put together, like the News Literacy Project and PEN America. The News Literacy Project’s Rumor Guard is a great place to start.

Consider making those explanations a standing part of a newsletter or social strategy — and even better, share them alongside resources when there is misinformation happening. Wouldn’t it be great if as people are learning from you about their government and elections, they’re also learning about how responsible journalism operates?

Go a step further by equipping people to create a news diet that works for them.

Make sure you’re not sending the message that more news is always better. Sometimes, offering a finite experience is a huge relief. (Hence the popularity of newsletters, right? A one-stop shop that can be consumed in one sitting?)

Offer people an on-ramp — and off-ramp — to a manageable relationship with the news. Show them where they should start, make recommendations for checking in, and acknowledge that it’s sometimes important (and encouraged) to turn it all off. Suggest newsletters, podcasts and other products that are thorough but not overwhelming. Consider offering this advice in a newsletter, an online story, a Facebook Live video or even on-air. Ask for their suggestions and questions. Acknowledge their experience and build trust by being a resource they can turn to.

Share what makes your news different

Whether we like it or not, we’re lumped together with every other information source out there. That’s why it’s so important for us to equip people to tell the difference between credible news and non-credible news – and share what makes our news trustworthy.

It’s rational for people to be frustrated by “the media.” Can’t we as journalists also point to irresponsible coverage as examples of what not to do? Our best bet is to explain and defend our own work — and in the process equip our audience to be more informed consumers of news.

We have many ideas for how journalists can do this, but a good starting point is explaining some key facts about your reporting process.

Covering election results

Building trust in your election coverage can take time and preparation, and a lot of the recommendations and suggested strategies in this kit work best when completed weeks and months before the election. If the election is just days away or happening today, here are some strategies you can deploy:

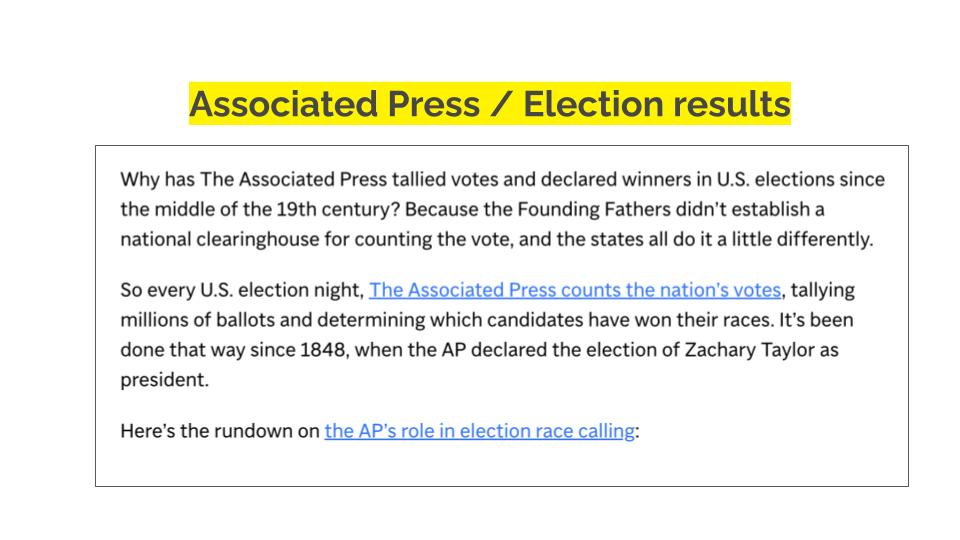

Explain how races are called

On Election Day (and the days/weeks before and after) we’re all likely to hear questions, misassumptions and accusations about election fraud. Embedded in those conversations will be some genuine curiosity and ignorance, along with bad faith misinformation and fear-mongering.

Are you ready to address them? Can you explain who you trust to call the elections, and how votes in your area are counted and reported? Have you prepped your community for how Election Day might unfold and when to expect election results? Here’s a great example from The Philadelphia Inquirer’s Jonathan Lai.

The Associated Press has invested in explaining their (immense) role in the process. Here’s their 2024 election hub, where you can browse dozens of explains about how their election process works.

The below section also includes suggested text you can copy and use to explain how races are called and votes are counted, and respond to common election questions and misinformation.

Whether you have your own explainers ready, with information provided by your local elections officials, you’re relying on the AP, or you’re using our pre-written explainers below, we advise you to be ready to share them routinely in two primary ways:

- In your day-to-day coverage, anywhere you’re sharing election news. That means putting explainer language and links in boxes and editor’s notes, and also in newsletters and broadcasts. Don’t overlook the idea of a simple parenthetical within a story to offer context like this.

- In comments, responding to questions, accusations and misinformation. Yes, this takes time. it is our sincere hope that you can carve out time on Election Day to actively explain and defend how democracy works, wherever questions are being raised.

Provide support, not anxiety

Waiting for and watching election results roll in can feel increasingly chaotic and confusing.

As journalists, it’s not our job to protect the public from information that might increase their stress. But it is worth considering whether our journalism contributes to or assuages their anxiety.

We can choose to air a highlight reel of chaos, or we can choose to provide calm, measured context. As an election unfolds, that means reminding the public what we expect to see, what is unusual, what safeguards are in place, how long it will likely take for votes to be counted and what they can do to protect their own vote and stay informed.

A few questions we suggest newsrooms ask:

- Have you set expectations with your audience ahead of the election that it may take days or weeks to know the result? Do you know the schedule by which your local election’s office will release election results?

- Do you have other useful, non-anxiety-inducing content ready during unclear outcomes (E.g., context pieces, history, explainers, listening to community)?

- What graphics will you present on election night? If you are using a map, what will be your thresholds before coloring in a state?

- Do you have experts at the ready locally to talk through procedural next steps and generate calm?

- How will you frame your coverage around the functioning of American democracy rather than only around parties — and around winners and losers? Will people who turn to you for coverage walk away with a better understanding of how democracy works?

We also encourage newsrooms to examine how much they are using “breaking news” labels and sending alerts. Watching election results can be chaotic and confusing, but it’s not really breaking news. Overusing that term can add to the hype, anxiety and polarization, and turn people off fro consuming responsible information. Instead, let’s think about how we can provide calm, helpful context . More on how to do that here.

Journalists can play an important role in helping set accurate expectations for how elections works and how races are called. Trusting News has created copy/paste language you can use to help set these expectations and also respond to common questions and accusations newsrooms often hear during major elections.

Feel free to copy, adapt and use any of the below explainers in your own coverage. This language can be added to stories as editor’s notes or shaded/pull-out boxes, go inside stories on-air, published in social posts, included in newsletters and more. The language can and should be edited to reflect your newsroom values.

Find more suggested copy for how to respond to user perceptions from the 2024 election here.

Copy these explainers: Explaining how vote counting works

Why and how AP counts the vote for thousands of US elections.

Suggested language: The United States doesn’t have a nationwide body that collects and releases election results. Instead, journalists gather data from local and state agencies that report election results publicly. The Associated Press gathers this data and makes it available to the public and to other newsrooms, to count the votes and then declare winners. They’ve been doing this in presidential elections since 1848. Learn more about that role here.

If the polls just closed, how can AP already declare a winner? And Florida has nearly all ballots counted on Election Day, while California can take weeks. This is why.

Suggested language: Elections in the U.S. are highly decentralized and complex. While uncontested or landslide races may be called right after polls close, competitive races may take days, or even weeks to call. And while some states like Florida count most of the ballots on Election Day, other states, like California, can take weeks. Read more about the process of vote counting and how races are called here.

If we don’t know who won, that must be a sign of dysfunction or chaos.

Suggested language: Elections in the U.S. are highly decentralized and complex. While some states start counting mailed ballots before the election, other states wait until Election Day. While uncontested or landslide races may be called right after polls close, competitive races may take days, or even weeks to call. This is normal and it’s expected. Learn more about how states count ballots and how races are called here.

Copy these explainers: Accusations of a rigged election

The elections are rigged or there’s widespread fraud.

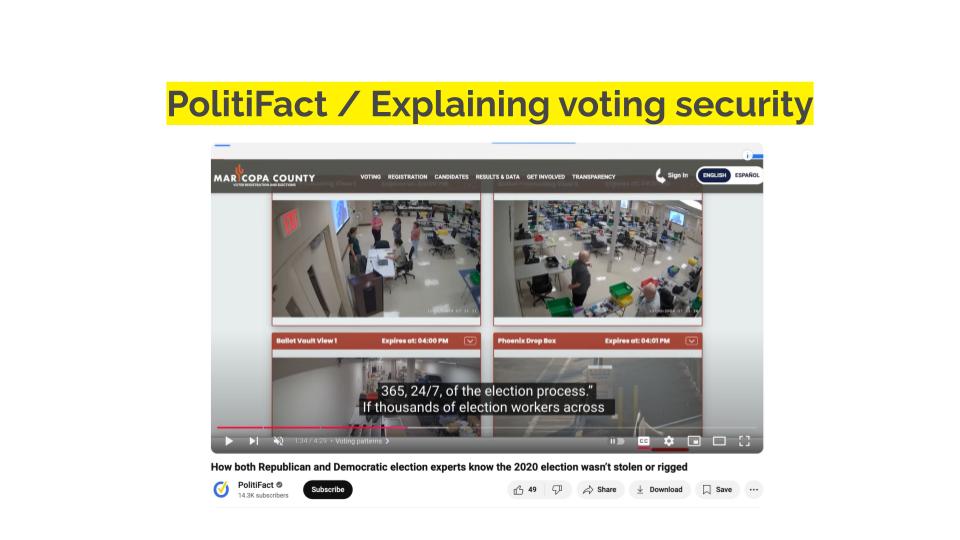

Note: Many people (more than a third in January) believe the 2020 election was stolen. So when addressing accusations of fraud, don’t just say the election is fair and leave it at that. Explain how we know that’s true and accurate, explaining the safeguards in place.

Some resources to help you debunk false claims of voter fraud.Reporter Isaac Saul at Tangle debunked a list of some of the most common election fraud claims.

- The AP published a story on voter fraud, explaining how rare and unlikely it is.

- This PolitiFact video explains how both Republican and Democratic election experts know the 2020 election wasn’t stolen or rigged.

- Here’s an example of how NPR did this last week, laying out some basic key facts about how the 2020 election results were upheld. (The audio version has a fantastic intro.)

- A state-by-state look at 2020 claims from the Associated Press.

Suggested language: Our voting process isn’t immune to problems. There have been occasional instances of voter fraud in the past, but it’s extremely rare, according to election administrators of both parties. When voter fraud does happen, there are many safeguards in place to catch it, and it’s usually detectable. You can learn more about the safeguards and election protection systems in place here. That being said, we are watching closely for any instances of voter fraud and will not hesitate to point it out if we verify that it’s happening. You can find up-to-date election information about polls in this area at [THIS LINK].

Suggested language: Our voting process isn’t immune to problems, and it’s likely some things may go wrong on Election Day — whether it’s long lines at polling places, running out of ballots or temporarily downed voting machines. However, these problems will not be unique to this election — there have always been glitches in our election process. Despite some imperfections, the system reliably produces certified outcomes thanks to many safeguards in place. Read more about it here.

Copy these explainers: Election Day claims

Suggested language: Is there any truth to claims that dead people and noncitizens are voting, that voting machines are flipping votes and that there’s widespread fraud in how votes are cast and counted? No. Here are some Election Day answers from PolitiFact, an independent news outlet that has been fact-checking US politics since President Obama was running in in 2007.

The 2020 election:

Suggested language: Despite continued false claims, there is no evidence that fraud influenced the outcome of the 2020 presidential election. President Biden won the Electoral College with 306 votes, compared to President Trump’s 232. This story from the Associated Press walks through the results, including recounts and reviews conducted in battleground states, all of which confirmed Biden’s victory.

Copy these explainers: Fears about misinformation

It’s impossible to know what’s true.

Suggested language: We get it. There’s a lot of information out there right now, including misinformation and conflicting messages. As journalists, it’s our *job* to sort through it all, and we still get overwhelmed. Some tips that might help: Be wary of analysis from people who aren’t doing their own reporting or aren’t citing their resources. Be mindful of whose job it is to provide straightforward information and who’s instead trying to influence your thinking. And double-check what you’re seeing online. If you see video clips or images that seem alarming, check to see if those have already been circulated in the past and are being used out of context. At [publication name], we are working hard to provide fair coverage that makes it easy for you to find accurate, fair information. If you have questions, or think we got something wrong, reach out to us [here].

Copy these explainers: Your commitment to balanced, fair coverage

Assumptions about one story vs your whole body of coverage

Suggested language: People usually land on a news site through a specific story, and they will not automatically understand the full breadth of your coverage. Include an editor’s note or box explaining your commitment to fairness and balance across sides of an issue or political viewpoint.

Suggested language: This story is part of our continuing coverage of the 4th District Congressional race. We aim to provide fair, complete coverage of this race across issue and political party. Find coverage of (the other candidate, these other issues in the race, etc.) here.

Accusations that you aren’t reporting on something specific because you’re biased or pressured by officials.

Suggested language: At [newsroom], we’re a local news organization focused on how local elections will impact people in this region. That’s why you won’t see us covering the national/state elections as closely. [You can go here for that coverage…] If we’re not reporting on something, it doesn’t mean we’re hiding anything or being pressured by the government not to report it.

At [publication] our goal is to provide voters in this region with accurate, fair information. Throughout the campaign, we’ve covered candidate rallies on both sides. You can find that coverage [here and here]. We have reporters and photographers at both candidates’ watch parties tonight. You can find that coverage [here and here]. If you have questions or think that we’re missing something, please reach out [here].

See how other newsrooms do it

Here are examples of how newsrooms have build trust with their election coverage. For more newsroom examples, check our our newsroom example database.

We’re here to help!

Congratulations on getting this far in the Trust Kit! We know taking the steps to earn trust isn’t always simple or easy. It takes time and often requires a shift in newsroom routines or workflows. Any progress you make on implementing strategies in this Trust Kit should be celebrated as a win!